Late in the fall of 2005 I was working backstage as a costume assistant in a play which had little use for me. Costume changes were few and far between and the actors were fully capable of donning their accoutrement without help from any one of the five assistants in the dressing room. As the days dragged on, we assistants became bored. There was nothing for us to do. We lounged around talking about anything and everything. We gossiped, we argued, we shared our secrets.

It was during one of these conversations I was told I had an astrological destiny.

Having been raised on a farm in Southeast Iowa, the son of a reading teacher and a former science instructor turned electrical engineer, I had little interest in the occult, and little use for the quixotic. But one young woman (who clearly didn’t share my grounded corporeal upbringing) insisted my future was written in the stars, determined by the specific orientation of the cosmos at the time I came into the world. I scoffed at the notion, and tried to change the subject, but she persisted. “You are a Gemini,” she told me, in a grave tone, “which means you are mutable. You have a dual nature.”

She pointed to my eyes, which are two different colors. “Your heterochromia signifies that you express these bilateral qualities to a greater degree.”

She continued on at length, revealing to me the “secrets” of my nature and the future available to me. She pressed me for the details of my birth, and went on and on about what I could expect of myself and the life that lay ahead of me. I found her conviction unsettling, and it was all I could do to keep from walking out of the theater altogether. I began searching the dressing room for something needing to be done, for some way to escape her fixation, but I failed to shake her. The remainder of my evening was spent as the subject of her prophetic “gift”.

When I returned home I found I couldn’t get to sleep. I was upset. Angry, actually. Not because I had been hounded for hours on end by a person whose beliefs were different than my own, but because her beliefs proclaimed I could only ever be one kind of person. The expectations she had for my life led down one road — they only gave me a single option. They created a framework designating the breadth of my independence which was dictated, apparently, by a collection of celestial bodies overhead. I saw this framework as a cage, a prison. I saw it as despotic, placing me in a yoke restricting the full expression of my potential. In a sense what she had told me was, “this is who you are. You will never be anything different. You can never be anything different. Your trajectory is fixed.”

As I continued to reflect on what she had told me, I realized this fixed notion wasn’t an uncommon one, or one found primarily amongst those who adhere to New Age systems of belief. It was one that permeated every aspect of culture and society. Think about the many “truths” we hold to be self-evident (say, for instance, within the limited scope of governance) and how those truths have evolved over time. Often in retrospect we discover these old truths were not grounded in empirical fact, rather they were arbitrary preferences enforced to provide an authoritative veneer in a complex world.

This shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me, however. We humans find surety comforting. Even our biology has evolved to quickly recognize broken patterns — a skill-set especially helpful for survival. We prefer knowing what will occur the moment following this one, and this preference drives our behavior, leading us to create mental models that dictate interactions with the world around us.

But what happens when these models carry over to domains with nothing to do with our survival? The result is something thinkers, researchers, entrepreneurs, and artists have been struggling against for the entirety of the historical record.

And Noelle Weimann is one who knows this struggle all too well.

“My darkest moments with art came when I took a career shortly after college,” she told me.

Raised in Connecticut by parents who were art dealers, Noelle grew up surrounded by art. Collectors often visited her family home, which was full of an ever-changing selection of artwork. And Noelle would accompany her parents on trips to New York City several times a week. There she spent hours exploring museums and galleries. She did master studies, sketching work she had seen — learning from the artists whose art had passed in front of her eyes. And those collectors who happened through her home, they took notice. Her first nudes sold when she was just 18 years old.

“[It] was a great feat for me,” Noelle said. “It was small money, but the feeling that my art had been appreciated by another human — seen, wanted — set my soul on fire.”

She attended Southern Connecticut State University where she earned a BS in Oil Painting and a BA in Art History. There she had the opportunity to learn under the tutelage of a number of recent graduates from Yale University. “Many of them were feeling out the full time artist life,” Noelle told me, “teaching their students how to source materials from scratch, build their own canvas and hit the art scene using as little money as possible.” Their influence on her artistic development was — using her word — monumental.

Spend time knowing oneself.

— Noelle Weimann

Noelle had the background. She had the pedigree. She had the connections and the training. By all accounts she had the makings of a successful career in the arts straight out of the gate. But instead, after graduation, she did what many creative people do when faced with life outside the university campus: she chose a different route. Noelle went into social work, “to make money.”

“I felt the pressures of society,” she told me. “The East Coast values hard work and the preservation of wealth above most things. This judgment weighed hard on me and I succumbed.”

She didn’t actively paint for the next ten years

One of the most common depictions in our society of someone who has chosen to pursue a creative career can be found in the trope known as “the starving artist”. Deceptively simple at first blush, the image of “the starving artist” actually reveals quite a bit about societal priorities and expectations. Clearly, it serves as an endorsement of full economic participation in a very specific manner. It enshrouds art beneath an obfuscating narrative stripping it of its worth. In other words, it discourages one from pursuing a life in the arts with the implication that the product of such a pursuit will not be seen as anything of value, thus one will not be able to sustain one’s life at even the most basic level (I.e. you won’t be able to eat!). (There is another implication here, which is that there is a level of income above which people can be seen as good contributors to society — all those who fall below that level are stigmatized, labeled as bad actors, lazy, etc.)

While it is true most artists do not earn millions of dollars, it is simply not true that artist cannot make a decent living wage doing what they love. Art is everywhere, adorning the trappings of our lives, driving the aesthetic experience of the websites we visit, the films and television shows we love, the games we play. It is so integral to our everyday lives that it can easily become invisible. Look around you, at the products surrounding you, and think about the artists, craftsmen, and creative people who had a hand in bringing them into this world. The truth is not that art is something without value, it is something of incredible material worth — equaling an economic contribution ranging in the billions of dollars.

But the falsehoods contained within the trope of “the starving artist” do not end there. Contained, also, within this toxic axiom is another destructive lie: that art can only be one thing.

This, too, Noelle has struggled against.

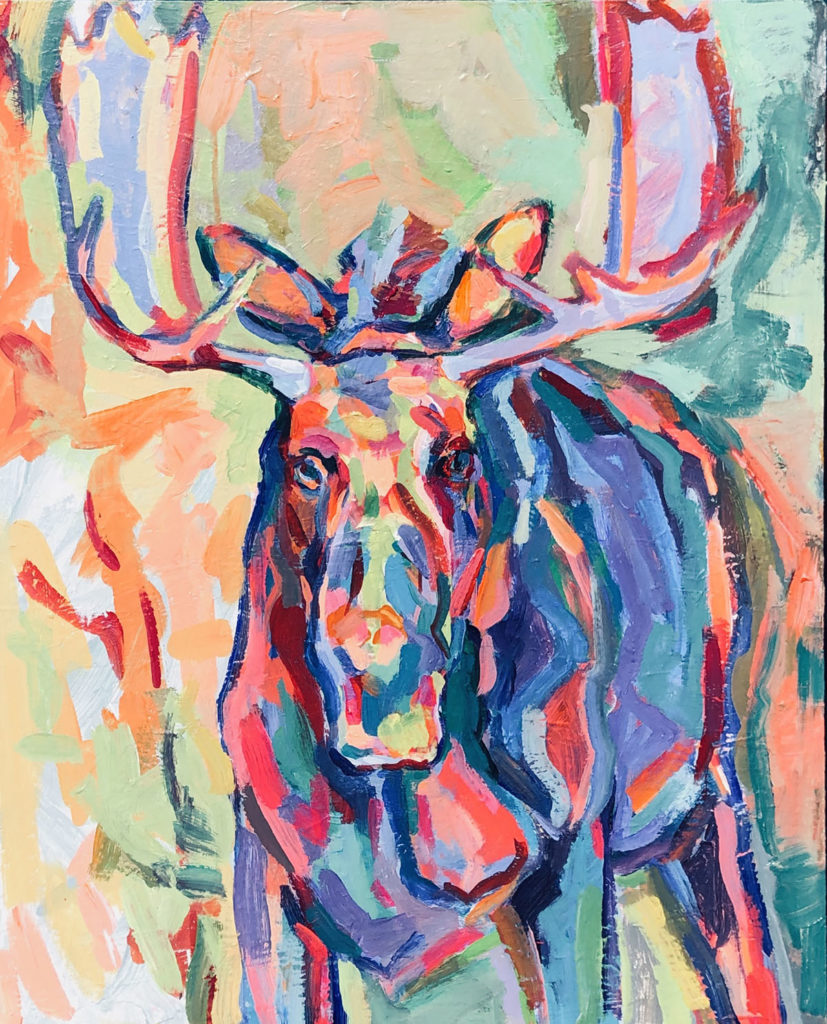

When she returned to painting Noelle did so with urgency, driven, perhaps, by the years she had lost in pursuit of a profitable career elsewhere. She focused on plein air and figurative paintings around her new home of Lander, Wyoming, deliberately creating work in a limited time frame to “[capture] the quick movements, energy and personality of [my] subject.” Influenced by the work of early 20th-century Fauvists and later Postmodern movements, she began exploring space using vivid color, emphasizing emotion by using exaggerated light and saturation. The results were bright and expressive, textural in structure and form, with bold brush strokes layering the work like a topographical map of her active mind.

“I paint the way I do, with the colors I do, because that is the way my brain processes the values it’s reproducing,” Noelle said. “I feel at home, normal, accepted.”

Creating work in this way struck a chord deep within her, so she continued to pursue that feeling, pushing past traditional boundaries to capture the essence of it with each new piece.

It was a way of producing work that I was quickly drawn to.

The first of Noelle’s works I saw was hanging at Lander Bake Shop, a place I gravitated towards shortly after moving to the area. The piece was large, a vertical composition that commanded attention through its size and bright colorization. And as I inspected it I became overwhelmed by the authority of Noelle’s brush strokes — any artist with the confidence to lay her brush to the canvas with that kind of certainty could only have been, in my mind, an intimidating figure. I spent the next several months dreading the specter of Noelle until we met by chance out painting in Sinks Canyon State Park. I discovered she was, in fact, an amiable person — and we hit it off straight away.

This misreading of Noelle on my part probably wouldn’t come to her as anything unusual (I have yet to admit my initial fear of her to her). She is probably used to just that sort of thing. But while I was daunted by her work, Noelle admits that others can sometimes have quite a different reaction: confusion. This isn’t due to the quality of her art, however, but something else, something more odious — something related to the fixed notion I mentioned earlier.

This thing I’m referring to is the idea that art can only be one thing.

Think again about the trope of “the starving artist”. Largely the product of 19th century romanticism, and dominated by allusions to such tragic figures as Vincent van Gogh, the narrative this trope depicts is one wherein the artist must needs suffer (typically in material fashion) in order to create meaningful work. Another implication here is that there is such a thing as meaningful creative work, which is often interpreted in its original sense as fine art. Thus fine art is the only kind of meaningful creative work one can do, and it naturally follows what constitutes fine art is something similar to the original traditionalist or romantic art out of which this notion emerged in the first place.

Therefore, true art, or good art is something definitive and implacable.

It is something fixed.

This notion is a fallacy that has been debunked countless times over the years, but one which the uninitiated still hold as a truism. It is a myth found in every corner of society, but one which holds great sway particularly in areas like the rural West where traditional ethos is slow to evolve. In a region where there is still a strong devotion to classic realism and romanticized visions of the West, work like Noelle’s offers a daring contrast. But the idea that a departure from the norm is something unusual is, frankly, ridiculous. Artists have been making these departures since human beings began making art, it’s part of the nature of the work.

To illustrate this, let’s discuss the Fauvists.

Fauvism was an art movement championed by a group of early 20th-century artists known as les Fauves (”the wild beasts”) whose inspiration came from artists such as van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, and Cézanne. One of this movement’s principal proponents was Henri Matisse, who became it’s de facto leader, establishing the use of intense color as a way of communicating an emotional state. The Fauvists divorced color from its traditional representational purpose with this intention in mind, and simplified their compositions to create a strong, unified overall vision on the canvas. The resulting works were bold and highly saturated — and something the art world had never seen before.

In fact, their departure from traditional norms is what earned Fauvists their name. So scandalized were the critics of the time that one, Louis Vauxcelles, called the artists wild beasts, a name which stuck. But the horror traditionalists felt, and their objections, did little to curtail the burgeoning movement, and today Fauvism is recognized as an important precursor to modern art, having directly influenced such artists as Pablo Picasso, who with Georges Braque later developed Cubism and who, even later, was tied to the surrealist movement, a major figure in which was Salvador Dalí, who influenced the modern artists, Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons… and on and on.

As you can see, the ideas never stopped evolving — art exists in a never ending process of development.

What I hope to illustrate here isn’t so much the importance of a specific art movement, but the fact that art has never been in any way a fixed thing. There has never even been one definition of what art is, what it should do, or the markings of what a quality work of art should be. Even scholars and aestheticians who’ve studied this for years on end mostly disagree. There has never been, nor will there likely ever be, any consensus about the definition of art, and therefore there will likely never be any consensus about what constitutes good art (because how can you reasonably apply a value judgment to a thing when you have no way of expressing whether that thing is even a thing at all).

The feeling that my art had been appreciated by another human — seen, wanted — set my soul on fire.

— Noelle Weimann

What it really boils down to is preference — and like most preferences, the preference for a specific kind of art is not influenced by any sort of empirical system for evaluation, rather it is influenced by a simplified mental model that can easily be applied to assist in the processing of stimuli (in this case, art). So that which is different isn’t necessarily worse, it is simply unfamiliar. If we dislike a particular work of art, but can’t express the specific reasons why, there is a good chance that the problem lies within ourselves rather with what it is we’re faced with. It is more likely our feeling of aversion has more to do with our discomfort regarding something that sits outside the bounds of the familiar than with the inherent qualities of the work itself. An interesting takeaway from this realization is perhaps the next time we find ourselves reacting negatively to some piece of art, instead of heaping derision and scorn upon the artist we should take the opportunity to reflect upon what those feelings reveal about the inner workings of our own minds. (for more on this, read my article on attunement) I think we might all be the better for it.

To many artists — those who have a desire to create work that is a departure from the norm — the inevitable resulting antipathy from such a departure keeps them from carrying it out. What would it mean for their careers? Their legacy? Taking such risks could mean a loss of income or it could mean alienating a hard won collector-base. Shrugging off the fixed notion of what it is they are expected to create is an intimidating proposition. But Noelle couldn’t have it any other way. She views her work as an authentic extension of herself, and she encourages everyone to find space within their own practice to do exactly that. “Spend time knowing oneself,” Noelle advises. “Build a quiet and deep confidence by spending time alone. Focus on exercises that make you live in the moment, that make you present. Listen to your feelings. Do not torture [yourself by] being afraid of what others think.”

Contrary to what traditionalists of the moment might think, this is not something to be feared. This is not an iconoclastic call-to-action. It is a reminder. The world is complex and in an ever-changing process of evolution whether we like it or not. We are able to live more honestly when we acknowledge this fact, not only in our minds, but when we reflect that realization in the choices we make.

There is space enough for us all to explore.

Let’s see where it gets us.

Believe it or not, there is a way to celebrate the traditional without being antagonistic towards the contemporary (and vise versa). It is a matter of choice, a resolution we can make to acknowledge the presence of something new without being intimidated by it, to hold space for it in a way that allows us to react authentically to it without our emotions being hijacked by the negativity we find in discomfort. In this way we give ourselves the freedom to grow as individuals, to break the chains of dogmatism — to honor the many wonders of this world we live in and the many evolving stories we take part in during our lives. Our trajectories are not fixed. They never have been. So why restrict our potential?

Life, as well as art, holds endless opportunity for growth.

We might as well make the most of it.

Noelle Weimann’s work can be found at Alchemy Artists’ Cooperative and Sweetwater Studio in Lander, Wyoming.

Postscript Note: It’s important to acknowledge the fear artists feel regarding finances comes from a very real place. True, many artists struggle when it comes to financial security. Many work other jobs to maintain their particular standard of living. Most will never achieve the acclaim of their idols. These are realities. When we use the trope of “the starving artist”, it is to these realities we also refer — but once again, these realities reveal our fixed notion about what art is and how it can be incorporated into our lives. I will be writing more about how this fixed notion restricts artists’ ideas about how it is they can and should conduct themselves in the marketplace in a later post.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.