In an article published September 13, 2019 on ESPN.com, international sports writer Aishwarya Kumar detailed an intriguing fact from the world of high-level chess: during competition, players were burning tremendous levels of calories and routinely losing weight. Strange as it may seem (since it appears for all observers to be a relatively sedentary endeavor) the physiological response to chess tournament play was comparable to the physically demanding world of elite athletics. In 1984 defending champion Anatoly Karpov lost 22 pounds during the World Chess Championship. In 2004 Rustam Kasimdzhanov walked away the winner and 17 pounds lighter. Today, American grandmaster Fabiano Caruana only becomes worried if his weight drops more than 15 pounds over the course of a tournament. Anything less is considered normal.

Renowned neuroendocrinologist Richard Sopolsky, whose work at Standford University includes the study of stress in primates, spoke to Kumar about the phenomenon. According to Sopolsky chess players can burn up to 6,000 calories in a single day of tournament play. If we take into account the daily caloric average a person consumes (around 2000 calories), the gravity of that figure becomes clear. At three times the daily average, the energy expenditure chess players experience is no joke. It is a serious toll. And these days it’s of such concern that grandmasters have begun training their bodies as well as their minds in order to prepare for the rigors of tournament play. That means players are running, weight-training, and hiring nutritionists and personal chefs to ensure they’re in peak shape and ready to perform. All this because of a board game.

So why does chess levy such a cost?

According to Sopolsky, grandmasters can experience elevated blood pressure for hours on end, similar to competitive marathon runners. Heart rates rise, which forces the body to produce more energy. Sleep patterns are disturbed and appetite is diminished. The mental strain, while unobservable, causes a cascade of physiological effects which come at great expense to players. It is insidious in that way. The demand on the individual is concealed, obscured by a still, focused appearance.

Effort is disguised beneath the veneer of effortlessness.

And that should make us think. What else could we be so very wrong about without realizing it?

Talent, actually, is another subject that illustrates just how wrong our assumptions can be. Like how we assume chess players have it easy, those we deem “talented” are similarly given short shrift. In the world of art, “talented” artists are those who were supposedly born with innate abilities. Their skills seem inexplicable. Their creations emerge almost as if by magic, appearing with such evident ease that it couldn’t be anything but instinctual. While we may sit in wonder while observing a particular piece, rarely do we meditate on the exertion required to produce it. Given what we think we know about talent, it doesn’t seem necessary. We are content to believe the creative process is somehow miraculous, that its power is endowed upon a privileged chosen few who have been lucky enough to inherit it. The unseen mechanisms of the creative act are, to our minds, emergent otherworldly qualities practitioners don’t develop. Instead, they are channeled through artists who only serve as intermediaries in an oracular process.

But is it really so?

Ask any artist and you’re likely to hear something different.

“The greatest misconception [I encounter] is that I am talented,” the Jackson Hole-based painter Kathryn Mapes Turner told me. “No. I am just blessed with a love of beauty. I don’t believe we are born with talent. We are born with a love, and that love, when cultivated, leads to the passion necessary to dedicate the time it takes to develop talent.”

Kathryn Mapes Turner considers herself a daughter of the Northern Rockies. She belongs to the fourth generation to be raised on the Triangle X Ranch in Grand Teton National Park, a premier dude ranch which has been in operation for over 90 years. Surrounded by the dramatic allure of Wyoming scenery, and under the looming peaks of the Teton Range, Kathryn learned to ride, and spent her days exploring the endless trails of the valley. She was educated in wilderness lore and gained an expert’s eye for landscape. A deep-rooted love of beauty developed. It grew, and that love set the course of her life.

“A place with such dramatic light and natural composition, gave [me] an intimate appreciation for art,” Kathryn told me. “I believe the valley of Jackson Hole evokes expression.”

She began studying art seriously in her teens. “At a young age, I was fortunate to meet some of the country’s best draftsmen and landscape artists,” she said. “It was in high school when I started studying with Skip Whitcomb, Ned Jacob and T. Allen Lawson.” Under their skillful tutelage Kathryn began to cultivate skills of her own. And those skills soon became clear to notable figures in the Jackson Hole community.

“When in high school, Bill Kerr, founder of the National Museum of Wildlife Art bought one of my paintings for $50 to put into the permanent collection of the museum,” Kathryn said. “That endorsement sent a strong message in support of my aspirations to be an artist.”

After graduation, Kathryn went on to study studio art at the University of Notre Dame. She spent an influential semester in Rome, Italy, and later studied at Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, DC, whose alumni include notable creators like David Lynch, Kerry Washington, Tim Gunn, and the MacArthur “Genius Grant” award-winning sculptor, Tara Donovan. Kathryn earned a Master’s degree, as well, from The University of Virginia.

“All of my teachers emphatically instilled the same advice,” Kathryn told me. “In order to learn how to paint, paint miles and miles of canvas. They all encouraged me to fall in love with the process of painting rather than the product.”

“Fall in love with the process of painting and that will give you the passion to put in the time it takes to reach excellence,” she added.

It is advice that leaves little room for any notion of intrinsic talent or magical abilities.

Hard work, it seems, is the key.

“A genius is not born but is educated and trained,” László Polgár once told The Washington Post.

Polgár, an educational psychologist by training, raised three daughters to become chess prodigies in a deliberate and rigorous training environment based on his personal theories of education. Convinced that he had discovered a common theme within the biographies of eminent individuals, Polgár, along with his wife, decided to raise children to become geniuses in their own right. Together, the Polgárs chose to train their daughters, Zsuzsa, Zsófia, and Judit, using an educational protocol of László Polgár’s own making. While Polgár believed his approach could be applied to any subject, he and his wife chose chess for their children. “Chess is very objective and easy to measure,” Klara Polgár, the girls’ mother, told Chicago Tribune in 1993. Given its clear rules and strict, unified enforcement, chess would provide the perfect vehicle through which to demonstrate the effectiveness of Polgár’s training regimen.

While some would come to question Polgár’s willingness to “experiment” on his own offspring, the results of his approach are difficult to deny. All three daughters achieved the rank of grandmaster. One became the Women’s World Chess Champion, one gave one of the strongest performances in chess history at the age of 14, and one is considered the strongest female chess player of all time.

Evidently Polgár was on to something, and what that is flies in the face of what we think we know about talent.

While we may be enchanted by the work of “talented” people, we shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss their efforts by way of magical thinking — by associating their abilities with intrinsic gifts. Seeming effortlessness generally disguises something more effortful. Sure, it can be easy to watch the performance of a prodigy and pass it off as the result of innate “talent,” but the example of the Polgár sisters should set us straight. Taken alongside what we know about the physical demands of tournament chess and the picture we get isn’t so miraculous. Accomplishment in this intellectual creative space isn’t a matter of muses. Instead, it follows effort. It takes time, dedication, and focus. It’s a matter of determination, and it comes at great cost. Calm demeanors and inexplicable creative leaps may suggest a story of inborn exceptionalism, but that story is incomplete and misleading. “Talent,” as we commonly think of it, is actually a veneer covering the truth behind performance.

In a sense, prodigies, eminent figures, and other “talented” people are performing sophisticated public-facing sleights-of-hand. They are illusionists revealing wonders, and these wonders appear to contain a touch of the divine. But the real source of their power sits behind a curtain just out of view. It is there we can find the whole story: the hours of practice and study, the countless failures and mishaps, the agony, suffering, obsession and joy which led them to where they ended up. As outsiders to their craft our minds do not perceive these mechanisms. We are content to assume the slivered, minimal anecdote we come across is, in fact, their story in its entirety.

But more often than not our assumptions are flawed. There’s always more than meets the eye.

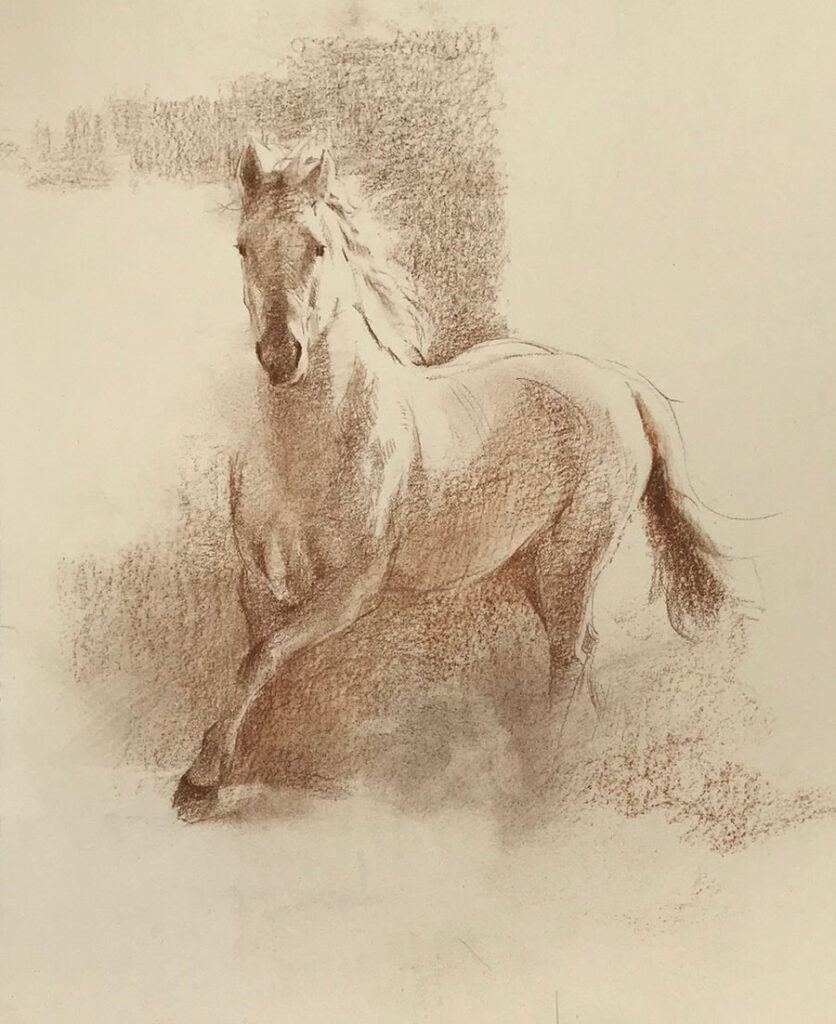

To my eye, a Kathryn Mapes Turner painting is like a lesson on perception. It is not a simple facsimile, an illustrator’s attempt at reproduction with photograph-like detail. Kathryn does not rely on supercilious technicality as a means to impress. Instead, her work is crafted utilizing mechanisms which parallel authentic experience, and thus it serves to illustrate meaning-making in viewers’ minds. Expressive strokes unify form and figure, and like specters emerging from a corporeal fog her subjects materialize on each textured canvas with life-like dynamism. Hers are not compositions that show you how to see, rather they show how it is seeing occurs, how it is experienced. They depict perception as a process, a content-arranging instrument each of us unconsciously rely upon to fit the innumerable fragmented stimuli of existence into a cohesive image we take to be reality.

Economy serves her well in this regard. A single contour, a softened edge, a subtle gradation. Distinct elements cohere in an interpretive way, leaving room for each observant eye to fashion a meaning all its own.

“In my work I want to capture the sublime essence of my subject matter and communicate that in my paintings as if it were poetry-distilled,” Kathryn Mapes Turner told me. “I want to leave behind a significant contribution to the collective experience of beauty.”

Likening her work to that of poetry is a fitting notion. Like the poet whose verse may flow with ease and grace when performed but whose days were spent agonizing over each single word, Kathryn’s lyrical work belies the effort it took to create. The eloquence contained within each mark may suggest unreserved freedom to the untrained eye — a talent born of transcendent gifts — but this is only a guise. Beneath it all is a deep well of experience compiled over years of effort, a skill-set hard-gained and well-earned but difficult to convey. Rarely do we glimpse this but through the rhythms of the work itself. And rarely do we allow ourselves to see even that, so consumed we are by its poetic allure.

It is easier to take it in, and explain away its genesis in terms of “talent.”

But that is an unkindness to the artist herself.

It does not honor the truth behind the work.

We have long understood that things are not always what they seem. Most of us know that what we see is not always what we get. We realize it is easy to fall prey to illusion and falsehoods, but still we convince ourselves that our observations, opinions, and instincts paint an accurate picture of reality. While some of this is certainly due to flaws in character, much of it is due to the fact we are built in a particular way that makes us vulnerable to deception. Our brains allow us to be fooled. Consider the fact that magicians, despite our knowing their intentions and despite our supposed modern intellectual sophistication, still manage to trick us by exploiting our biases and cognitive weaknesses. That magicians are still able to do this with relative ease is all the proof we need to show our mental faculties aren’t as up-to-snuff as we’d like to think they are.

Any surprise we register upon learning about the physiological demands of high-level chess is indicative of these same weaknesses. The fact that ESPN publishers thought chess-stress noteworthy enough to highlight in 2019 testifies to the persistence of them as well. Science has shown that our assumptions about chess are not just wrong, they are so wrong they land on the opposite end of the truth spectrum. High-level chess play isn’t child’s play, nor does it pose little health risk to the individual. Common opinion would have us believe chess is a frivolous pursuit, not even a “real” sport. It’s seen as an exercise for awkward nerds and absent-minded professorial-types whose physical exertion is limited to flipping the pages of some thick tome in a dusty library. But, as we’ve learned, that narrative couldn’t be further from the truth. Its physiological effects are on par with those experienced by professional athletes. It is a game-changing revelation, not just about chess but also about our error-prone perceptions.

Errors of this sort are not uncommon. We can find them in nearly every domain. They are a direct consequence of the way our minds are built, and will haunt us for the duration of our lives. Most of us are hard-pressed to accept this, but it’s high time we face this reality.

Even in an era in which we pride ourselves on connectivity and information-availability, on technical advancement and scientific breakthroughs, we still fall victim to the limited abilities of our evolutionary minds. We still make unfounded assumptions. We still tell ourselves convenient fictions. We still subvert our own interests because of ingrained prejudices. Even in this modern day and age our own beliefs cannot always be trusted.

And when it comes to “talent,” we are just as easily fooled. We trick ourselves into believing what we see is what we get and explain it away using magical mental leaps.

The danger we face by allowing our misperceiving minds to get the better of us, causing us to become lost in magical thought, is not inconsequential. In the case of the talent myth, we allow ourselves to dismiss the actual efforts of an actual person in favor of some easily-accessible fiction. And while there are those who delight in such a fiction, for most it proves a disservice. It undermines the dignity due to them, as well as the respect we should feel towards their effort and self-sacrifice. Also, it is unprofitably misleading. By painting a fraudulent picture that misguides those who would otherwise want to know better (particularly those who wish to follow a similar path) we actively participate in a form of subversion that helps smother potential before it even has a chance to develop. It is one of the unconscious ways we hold ourselves, and those around us, back.

The solution? Inquiry. Effortless-seeming effort should always be met with curiosity. It’s all too easy to fall victim to our own cognitive weaknesses when we lean on superficiality. We must learn to look deeper. Sure, the world is vast and even the foremost intellects do not have the capacity to understand everything. That is understandable. But it doesn’t exonerate us. To give up, to give in, to allow easy fictions to overtake our understanding of reality simply because the grand effort is difficult or beyond our capabilities is the mark of a cynical mind and a cheap soul. We live in the world we do, so we all bear responsibility to participate in it in as authentic manner as we are able. That includes taking time to understand, counteract, and rehabilitate the weaknesses that do us, and those around us, wrong. That means examination and investigation.

It means giving up magical thinking by learning to peek behind the curtain.

And it means giving the effort hidden beneath superficial effortlessness the consideration it deserves.

Take Kathryn Mapes Turner. Does her work unravel with ease, as the talent myth would have us believe? Is the process as effortless and insouciant as we might assume? Does she simply sit back, satisfied with whatever the apocryphal muse channeled through her brush? Let us inquire.

“In truth, I feel discouraged and dissatisfied regularly with my art,” Kathryn shared. “It is important to recognize that these feelings of insecurity are natural and also temporary. For me, the most effective way to move through these stuck times is to remember that I just need to show up in service to others by doing my best to bring beauty in the world.”

Like those chess grandmasters, there is more to her story than meets the eye.

The work and example of Kathryn provides us a lodestar. It serves to guide us towards a path of clarity. Kathryn models what it means to be an artist in practice and elocution with an authenticity that is refreshing and transparent. Talk of celestial “talent” is corrected, leaving room for an honest dialog about a career in the arts. She is clear and honest about her struggles, history, and development, and this opens the way for others to follow in her footsteps and helps reverse a widespread narrative that is misleading. Students are no longer be left to wonder if their struggles are mystical portents of inadequacy. Enthusiasts gain a higher level of respect for the reality of her work. Overall, it is a service to the industry, and service is something that acts a guiding light for Kathryn herself.

“We don’t need to be perfect,” she told me. “We just need to show up in service.”

It is a wise sentiment, and one we can all take as a lesson. And perhaps the greatest service we can all render involves how we approach our own perceptions. Perhaps we should all make a greater effort to rehabilitate our biases and learn to counter our own cognitive weaknesses. Letting go of our convenient fictions, assumptions and prejudices would certainly set the stage for a better outcome overall. We can appreciate the magic, absolutely, but we should always take a glimpse behind the curtain.

It is clarifying, and I think it would serve us all very well.

Kathryn Mapes Turner’s work can be found online at her website or at Turner Fine Art in Jackson, Wyoming. A solo exhibition of her work will be shown at Turner Fine Art beginning September 14, and running through October 31, 2020.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.