In 1921 the psychologist Wolfgang Köhler published Intelligenzprüfungen an Menschenaffen (The Mentality of Apes), a book summarizing his work studying intelligent behavior in anthropoid apes. It was an important milestone in the field of comparative psychology, and the book helped establish Köhler as among the most influential psychologists of his day. The studies he conducted were designed to answer whether animals behave with “intelligence” and “insight.” His approach, to construct an obstacle for his subjects to overcome. This usually meant placing a piece of fruit in his subjects’ view but beyond their reach. In this way Köhler would be able to observe and analyze their behavior.

In one experiment Köhler observed a chimpanzee named Sultan attempt to get a piece of fruit hanging from a playground jungle gym. It was too high for Sultan to reach, and after several attempts the chimpanzee appeared to give up, turning away to sulk. Then, after a few moments, Sultan sprang to his feet and stacked three boxes on top of one another, climbed them, and reached the fruit. The chimpanzee had improvised a solution in what appeared to be a moment of insight. Köhler described it as proof of animal intelligence — something that had never been recorded before in psychological literature.

Many of us will recognize Sultan’s behavior, the sudden flash of insight, a burst of inspiration. It is a common-enough cognitive phenomenon. Some refer to these as Eureka! moments. The ancient Greeks considered them gifts from the Muses. In the world of creativity, these fleeting incidents are known as “creative sparks.” But while the phenomenon itself is nothing extraordinary, the reason it happens — the specific neurological mechanism which leads to this kind of revelation — is still fundamentally a mystery. It is because of this mysteriousness that ancient cultures saw it through the lens of the divine, as an epiphany planted by some omniscient, invisible hand. But even today it remains just as enigmatic, a subject still under intense investigation. And given the brain’s complexity, it’s safe to say it will be some time before this particular revelatory code is cracked.

Still, it is among the most fascinating, and useful, cognitive phenomenon, a process which paves the way towards innovation. What domain hasn’t felt the effect of some pioneer’s seemingly miraculous leap? What achievement hasn’t been preceded by it? Few, if any.

Michael Blessing is a painter who has felt the benefits of inspiration in his own work. And it has led him to novel places and new heights. “I got a bit burnt out in 2018,” he told me. “It lasted until I had this voice shout at me, Put Neon light on your paintings!!! I saw pictures also. It came in whole. I’ve been on a tear since January of 2019.”

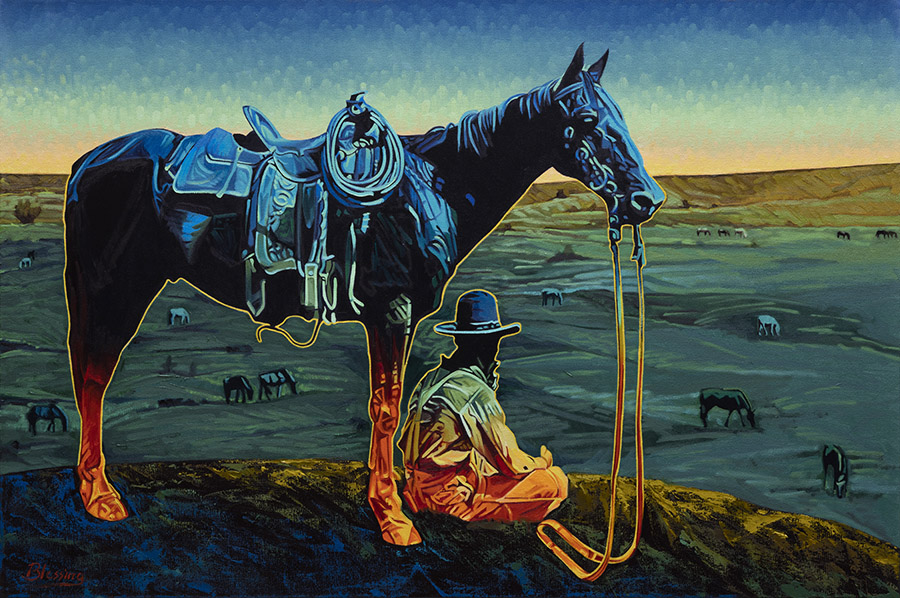

It was a luminous moment that led to his most recent series of trailblazing work with his triptych entitled “A Redeemable Outcome,” which premiered at Montana Trails Gallery in Bozeman, Montana in early July 2020.

Michael Blessing, who spent his formative years in Montana surrounded by, as he put it, “the land, the people, and the experiences that small town America provided,” didn’t begin his career as a painter. Instead, he pursued a Master’s degree in Music Arts and after entering the music industry, spent the next thirty years running two recording studios which he owned. “I took an art studio class in college back in the early 1980’s,” he told me, “but it wasn’t until I had a cancellation in my recording studio that I became fixated on art. Because of the extra time I had due to the studio cancellation I began drawing just for fun in 2002 with pencil. One thing led to another and by 2003 I was oil painting.”

While he studied privately for a time, and attended several workshops, the majority of Michael’s training in art has been self-directed. His ethic allowed him to make great strides, even impressing his early drawing teacher, who said, after seeing one of Michael’s drawings, “You could get into any art school in the country with this one drawing.” The instructor taught art at Montana State University, so Michael knew the feedback was meaningful. “I was stunned,” he told me. “I took him seriously and I was off and running.”

That ethic Michael exhibited early in his training continued, and the result is noteworthy. His work has become ubiquitous in the western art scene. Many people are familiar with his distinct, iconic style. And today, nearly two decades after he picked up a pencil and began to draw, he has racked up numerous awards, including Awards of Excellence from both Western Art Collector and Southwest Art Magazine, a 2017 Curators Award (Best In Show) for the High Desert Wildlife Museum Art Show, and a FASO BoldBrush Award. His exhibition experience is extensive, to say the least, and work of his is regularly featured in regional art publications. All told, Michael Blessing has had a notable and distinguished career in the arts.

While some might attribute his success and prolific nature to the magic of a muse, Michael sees it differently. He attributes it simply to good ol’ elbow grease.

“One misconception I often run across is that I just lie around and paint only when I’m inspired,” he told me. “My response is, making art for the art market is like having a working cattle ranch. You make a product, you take it to market and you sell it at a good price. In order to do that, [you] have to show up everyday and go to work.”

It is a sentiment which, interestingly enough, many distinguished artists have echoed over the years. Pablo Picasso is one who is well remembered for having said something very similar.

“Inspiration exists,” he quipped, “but it has to find you working.”

While the exact workings of inspiration still fundamentally remain a mystery, there are important things we do know about it. Most of that knowledge comes from examining the processes of eminent thinkers, artists, writers, inventors, and scientists. For years researchers have studied the behavior and delved into the minds of noteworthy innovators, and they’ve noticed a pattern in the way revelation comes about. Interestingly enough, it is not simply a matter of luck or waiting for it to strike, though this is the popular myth. There is, in fact, an order to it, a recognizable sequence. We may not know exactly how the phenomenon works or when precisely it will materialize, but research has revealed the framework upon which it is built, and it is this: inspiration requires preparation, and it requires effort.

Inspiration, as it pertains to art, is largely recognized as the impetus for creative innovation. It is the thing which leads the artist to create novel works of art. While inspiration certainly exhibits itself elsewhere (for example, a business leader may feel a spark of inspiration which leads to a unique business model), in the realm of art, it is generally understood that it is the thing that produces the subjective alignment necessary for the discovery of some new approach, technique, style, or theme.

But is it really so special? As it turns out, no.

Inspiration, or revelation, is just one step in a complex operation leading towards innovation. Research shows that innovation, doesn’t emerge “out of the blue,” it arrives after an established sequence. Traditionally the creative act through which innovation comes about is broken down into 5 steps. These include preparation, incubation, insight, evaluation, and elaboration. These relate to particular brain states, each of which work in conjunction to produce not just the sense of novelty known as the Eureka! moment, but also the drive one requires to follow through on one’s idea, to iterate, improve, and eventually finalize it. While we can see how insight is a necessary function of the creative process, it is clearly not the decisive one. It is a single numeral in a complex combination we use to unlock new domains. Without it the lock would remain unopened, but so too would it be in the reverse case. In the absence of insight, revelation, or inspiration, a creative result is unlikely. But on its own it amounts to nothing, and thus means nothing. The operation as a whole, from preparation all the way to elaboration, is what matters — the procedure is what produces the results.

The popular misconception that artists must lounge around waiting for the muse to strike is problematic in three ways. First, it gives disproportionate weight to a particular moment in the creative process, creating a misleading narrative about how the process is undertaken. Second, it undermines the importance of actions which must necessarily precede a moment of insight and follow it. And third, it diminishes the significance of the creative act as a whole, misrepresenting how each step functions in concert with each of the others. This leads to a perception that it is somehow unstable, frivolous, indulgent, or of little use to those with more practical concerns. Of course, this could not be further from the truth. Creativity is woven deep into the fabric of what it means to be human. It is an ability contained within each of us, and good thing it is. We wouldn’t be where we are today without it.

This disconnect in the way we think about inspiration likely stems from its mysterious nature, and from our own confusion about just how it operates. Also, given the unconscious nature by which it elaborates in our minds, it is easy to overlook just how commonplace it is, and just how it fits into the wider creative process. The challenge here lays in the fact that the only time we are able to consciously realize something is afoot is during moments of high valence, the electric-shock Aha! moments that leave an indelible psychic mark. But these represent the apogee of the experience, not the customary one which continually fuels the way we learn, ideate, and grow. Most of these routine moments remain largely hidden to us, but they are in no way less important or less impactful.

Regardless of whether we observe this process or not, it proceeds unabated, and informs the way in which we go about our daily lives. For some, of course, this process appears more pronounced and seems to point to something extraordinary, something almost magical. But this is certainly not the case. It may be, in fact, notable exceptions like eminent thinkers and artists are simply profiting off a habit which produces more meaningful, more recurring insights that are further developed through a dedicated ethic. In other words, they have a more refined ability to utilize a universal faculty, and the discipline to carry through on what it reveals to them. This sets the stage for positive feedback loops which quickly lead to an impressive volume of results, as new insights refined by disciplined action lead to additional insights and so on and so on. This might strip the overall process of its perceived magic, but that shouldn’t be what concerns us. Instead, what’s important is that it opens the process of innovation up to those who originally thought it beyond their reach.

So how might one facilitate useful insights that result in innovation?

Michael Blessing has a simple solution: be persistent.

“Don’t quit,” he advises. “You’ll never discover the sparkle of an undiscovered gem or a happy accident if you do.”

When one looks at a Michael Blessing painting, one can’t help but think of it as a visual metaphor for the creative act.

His motifs largely revolve around nostalgia, with striking compositions depicting historical figures and romanticized visions of the American West. The shape and structure of his figures, as well, hearken to the illustrative tradition popularized in The Saturday Evening Post and other publications of the early to mid-twentieth century, an era which helped glamorize the western mythos in the American mind. But unlike other artists, who are content to carry on this particular tradition, Michael delves deeper.

Layered upon these allusions to the illustrative lore of the West are elements from pop culture, iconic film personalities and the bright, buzzing color palettes pulled straight from old marquees and vintage neon signs. The luminosity is dazzling — the compositions glow (literally, in some cases, with the addition of functional neon light accents), giving one little choice but to bask in the illuminated subject matter. They are at the same time mimetic and amazingly original, perennial and modern. It is as though they issued out of some alloyed, in-between space, a hybridized conceptual illustration of the development of western culture.

But, to my eye, the metaphorical underpinnings are what give Michael’s work power.

Each composition appears to be a meta-analysis in and of itself — comparing, contrasting, combining, and reflecting upon distinct moments pulled from a cultural continuum. And it is done in a way that highlights points of connection and contention, revealing the unique trajectory of ideas over time and space. In that regard, Michael Blessing would seem to be a historian in his own right, an expert in the opus of the western mythos whose unique instructive methodology comes in the form of oil paintings.

But, even more, this approach parallels the iterative nature of the creative process.

Recall the pattern through which our minds develop innovative concepts, and it is easy to see it played out in a Michael Blessing painting. Ideas build upon ideas over time and in unexpected ways. They push and pull, stretch, distort, and finally fuse into something unique. They are referential without being overly-deferential, allowing space for conceptual evolution and growth, a sort of representation of the workings of an innovator’s mind. It is as if Michael Blessing were showing us the way, illuminating the potential contained within each of us. Each painting is a call-to-action, an appeal to our creative nature.

And the light.

The light, above all, appears as a beacon. It is as if we were witnessing a flash of insight, a moment of inspiration captured for all to see:

Eureka! depicted in oil.

The lesson we can take from Michael’s work as well as what we know about the creative process, is that it is a constant effort. It never ends, nor should it. Only through iteration will we find generative power, only through continual application will we find innovation. The popular image of the lounging artist who sits awaiting the muse is not an accurate depiction of the reality of creativity, nor does it respect its prodigious power, something that exists in each and every one of us. We must discard that notion. It offers us little utility.

Granted, a period of incubation is required before the mind is able to construct the connections required for insight (remember the pause Sultan took before solving the problem in Köhler’s ape study?), but this in no way requires us to do nothing. Incubation occurs even as we perform other tasks, be they mindless (like taking a shower or doing the dishes) or intensive, and it occurs during normal moments of restfulness. It is a process that continues within the nooks and crannies of our minds without us even knowing it. It cannot be forced. It responds in its own time and to to myriad inputs. Any notion that we must sit and wait for it to do its job is wrong-headed. In fact, such an approach may inhibit the overall process. Without proper preparation, incubation will slow and moments of insight may become less likely. Those we think of as the most innovative amongst us understand this — they are relentless, constantly feeding their curiosity and gaining experience, and it is because of this that they come to more innovative results more often. The more you prepare, the more likely you are to receive that creative spark.

Remember, inspiration takes preparation, and it takes effort.

Or, as Michael Blessing put it, “[you] have to show up everyday and go to work.”

Today it is easier than ever to resort to mindless leisure, to become distracted, to lose focus and go down fatuous rabbit-holes. It is easy, too, to externalize our own shortcomings, to attribute our deficiencies to something other than our own failure to properly prepare ourselves. But if we are to find some modicum of success in this wide, complex world, and progress in meaningful ways through creative problem-solving, we must find it within ourselves to take those preliminary steps which put us on a path more likely to lead towards success. There are many things we cannot control in life — not every idea we generate will result in accolades, nor will we be necessarily spared from grief and hardship. But we have within us an advantage ingrained into our mental architecture, a process inherited from hundreds of thousands of years of natural selection: we have our creativity, a process through which we can make incredible leaps and bounds, a process that can result in wonders. Inspiration exists in all of us.

But it must find you working.

Michael Blessing’s work can be found at Mountain Trails Gallery in Jackson Hole, WY; Huey’s Fine Art in Santa Fe, NM; and Montana Trails Gallery in Bozeman, MT. Follow him on Instagram and find additional information on his website.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.