I nearly drowned when I was eight years old.

It happened during a weekend sailing trip at a lake in a remote state park in Iowa. Too young and too inexperienced to aid in the operation of the 18-foot sailboat, I had seated myself at the bow while my father and brother took charge. It was an unfamiliar boat, a borrowed one, much larger than the small dinghies we had learned to sail only a few short weeks before. The wind was strong—too strong—and high trees along the lake’s narrow recesses caused the currents to shift in unpredictable ways. One moment it was smooth. The next, a blast of chilly air would fill the trembling sails and the boat would tilt at an unnerving angle. In retrospect, given the conditions, one might think it inevitable that we would capsize. At the time, however, it seemed like good fun. That is, until it wasn’t.

I awoke choking on water, my body seething with desperate energy beneath the cold press of the lake. For a brief, frantic moment, I had no notion of where I was or how I’d gotten there. I was only aware of the fiery pain in my lungs, the inexplicable spasms, the frenzy of fear animating my flailing body. Murk enveloped me. I floundered. Then I broke the surface and found myself beneath a dark, cave-like enclosure. Some small, still-conscious portion of my brain realized we must have capsized and I was trapped under the boat. The rest didn’t care. It only wanted to survive. I vomited water and screamed for help. There was no response. The only sounds I heard were my own rasping breaths and the angry slap of water. Wet sails wrapped my shoulders. I was alone.

After a few shuddering breaths I decided to escape the overturned boat. To my panic-stricken eight-year-old mind, I had no choice and little time. I thought the boat was sinking and taking me to the bottom. So I dove, struggling against the buoyancy of my life jacket, trying to thrust myself beneath the upside-down hull and to freedom. Sails pressed against my face and entangled my arms. I fought them off, swallowed more water, and reemerged beneath the boat, choking. I wailed and thrashed hopelessly at my fiberglass tomb. My heart punched against my ribs. Then everything went black.

When my vision cleared I was gazing at the open sky, clinging to the outer hull of the boat. Its rudder loomed above me like the dorsal fin of a giant shark. Lake water streamed from between my lips. I gulped the free air and bobbed like a stiff mannequin. A moment later my father found me. He flagged down a passing fisherman who lifted me into his boat by the scruff. My body shook as we slowly chugged back to shore.

Later I learned that my father was the reason for my miraculous escape. When we capsized, he and my brother had been thrown clear to safety. Once he realized I wasn’t anywhere to be found he tried diving under the boat, but his life jacket kept him above water. Unable to submerge himself, he began kicking beneath the edge of the hull to see if he could feel where I was. One of those kicks caught me in the chest and propelled me out the other side. I was stunned, bruised, and terrified… but I was alive.

That I am able to write about this experience is a testament to the role of luck in my life. If I had been knocked fully unconscious it’s doubtful I would have survived. 4 minutes of oxygen deprivation is all it takes to cause brain damage. That damage becomes irreparable after 10. Even if I had been recovered quickly, the time it would have taken to get me to shore and perform CPR meant I would have already been teetering between life and death. To make things worse, the nearest hospital was a half-hour drive from the park, meaning my life would have been in the hands of people who wouldn’t have had the skill or composure to ensure proper care. I am lucky, then, that I regained consciousness almost immediately after hitting the water. By pure dumb luck I didn’t bang my head hard enough to turn out the lights. That’s one reason I survived.

Another is that a chance kick from my father freed me before my panic led to further harm. In my desperation I had already tangled myself in the waterlogged sails of the capsized boat. Fueled by my unmanageable fear, a second or third attempt at escape could easily have left me exhausted. Unraveling myself from the snare of rigging or the grip of the wet sails might then have been impossible. In my state, if I had remained trapped beneath the boat for even a few minutes longer, it’s likely I would have drowned. Quick thinking on the part of my father—and a randomly placed kick—is one more reason I’m here today. Lucky, indeed.

At this point it should be clear this account of my close encounter with death is much more than a quaint (albeit cheerless) anecdote. Instead, it is a meditation on randomness and chance, and the way these phenomena can have drastic effects on the outcomes we enjoy (or don’t.) As I’ve already described, luck can mean the difference between life and death, but to assume it doesn’t have similar profound effects on other aspects of our lives doesn’t make much sense. Clearly we don’t choose our parents or our economic status at the time of our birth. We are lucky or unlucky in that regard. As we grow and develop we don’t choose the specific opportunities that make themselves available to us, either. And later, in our professional lives, luck continues to play an important role in how our careers advance (or don’t!) Chance occurrences may result in significant purchases, accolades, press, and recognition that may well turn out to be life-changing. The fact is, the presence of luck is a lingering one for each and every one of us. We cannot escape its grip.

So, the question is…

Do you feel lucky?

These days, talk of luck is largely verboten, or when it is discussed it is with a level of discomfort that makes meaningful conversation nearly impossible. Unless one is referring to games of luck (such that can be found in casinos), good fortune—especially as it pertains to one’s life—is rarely acknowledged. There are some who have made attempts to bring the role of luck in our lives into modern discourse and debate, but they’ve largely been met with resistance. For every person who ascribes favorable outcomes to luck and circumstance, there are more than a few who claim personal choices, skill, and grit are really what matter. Luck has become a hotbed issue, with devotees on either side of the spectrum squabbling over its relevance. But should it be so controversial? Is it appropriate simply to pretend chance has no role to play in the lives we lead? Or can acknowledging it be impactful? Does talk of luck lead individuals to put less effort towards their goals? How, indeed, can we discuss the profound effects of luck in our daily lives without undermining the importance of personal responsibility?

While it would be valuable for these questions to be addressed at a society-wide level, those of us in the arts would do well to seek answers out for the good of our own domain. Given the high hurdles and extreme hardships those in creative fields face in our modern economy, a clear and honest conversation might help struggling creatives distinguish phenomena they have no control over from those areas in their life and practice in which they do. Dejection and cynicism are the natural by-products of a process dominated by wistful dreams of lucky breaks that never materialize. By helping creatives acknowledge the role of fortune in their lives, we may free them from that particular gloomy psychological prison so they may pursue their goals with a level of clarity, grace, appreciation, and contentment. The work they produce will certainly be better for it.

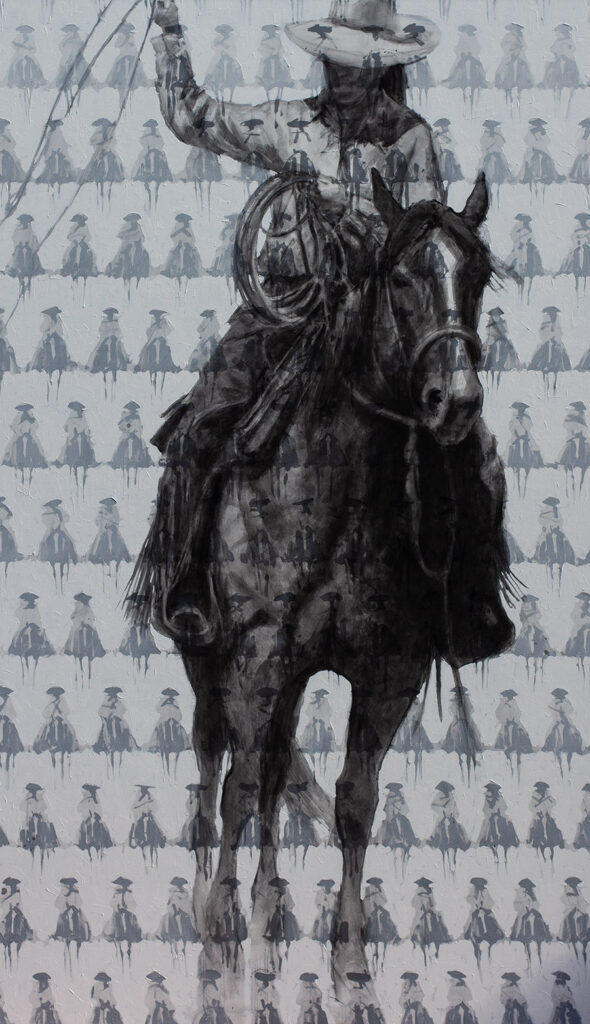

Colorado-based painter Duke Beardsley is an artist who freely acknowledges the role of luck in his own career. The gratitude he feels for the life he’s been able to lead has even seeped into his body of work. His paintings are bold, bright celebrations borne out of love for his subject-matter, something that hardly would have emerged if he’d been consumed by negativity and pessimism.

“I’ve been unbelievably lucky,” he told me in a recent conversation. “Anyone who’s had any success… as an artist, in my opinion… does owe a great deal of respect to good fortune.”

Despite being drawn to art at a young age, and later attending ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, the idea that Duke could make a living in fine art wasn’t something he entertained until he was about to strike out on his own. “The notion of getting paid to become what some people would call a ‘gallery artist’ didn’t really occur to me, to be honest, until I was just about to graduate,” he told me. “Because of the nature of the school, and the nature of my peer group and friends in my program, there was a lot of pull and energy towards corporate entertainment art.” Companies like Industrial Light & Magic (a motion picture visual effects company founded by George Lucas, creator of Star Wars), DreamWorks (a feature film and animation company founded by Academy Award-winning director Steven Spielberg), and Disney were among the notable places ArtCenter graduates might expect to find employment once their training was complete. But Duke’s heart lay elsewhere. “There was a very strong pull for me to come back [to Colorado],” he said.

His first solo exhibition followed shortly after he returned to his home state, at a gallery run by Elizabeth Schlosser in the Cherry Creek district of Denver. His introduction to the gallerist and influential historic preservation advocate came by way of the woman he was dating at the time. “[Elizabeth] said ‘Hey, let’s try a show when you get out of art school,’” Duke told me. But, according to him, the prospect of making a career out of exhibiting art still hadn’t taken hold. “It was just a great idea for the summer out of art school,” he said.

As it turned out, his first exhibition was a success. “We put forty-some canvases up and most of them were little and dashed-off, but we sold almost everything,” Duke told me. “It seemed like something that was like, ‘God, could you imagine being so lucky to do this again?’ But more importantly it opened some doors that became really significant. It introduced me to the powers-that-be at the Buffalo Bill Art Show in Cody, and it introduced me to the powers-that-be at Coors Western Art Show here in Denver. That year was symbolic. It was 2000 or 2001 that I was in both those shows for the first time, so [the first exhibition with Elizabeth] really did launch the energy to try some bigger things, and when those fell together and worked out, then it really started to roll that this was something that I should give a lot of energy to.”

And once Duke began to devote more energy to a career as a fine artist, valuable wisdom came to him by way of a family friend, a businessman who sat him down to go over basic business principles, as well as his own father, whose down-to-earth advice stuck with him, providing the foundation for Duke’s systematic and grounded approach to pricing and business. “He used to say, don’t think for a minute you know what this is worth. Market is what market will bear, and it always will be,” Duke said. “He was right. This is business and business doesn’t suffer fools, and the biggest fool in business might be the one who has an expectation for how it’s gonna go. Look at the stock market, it teaches us that daily.”

Duke took those lessons to heart and used them to help craft a strategy that would allow for a sustainable, long-term career. “I came up with a very conservative price-increase plan to take tiny steps up, and we stay on each step for a long time,” he told me. “It’s proven to be, I think, right for me, first and foremost, but also for my dealers and collectors.” With this approach he frees himself from the peaks and troughs of a career yanked around by the whims of chance, while still allowing his collectors to benefit from the gradual appreciation of his art. It also allows him to keep offering work to collectors from all walks of life, something that would be impossible if he’d tried to profit off spikes in popularity—a move many artists fall victim to, only to find themselves priced out of the market and worse off when that popularity fades.

“If you lose sight of the idea of how much money $5000 is to the average person, I think you’ve left the ground,” Duke told me, referring to another lesson his father imparted to him. “Parting with $5000 for a piece of art is an incredible luxury—an incredible, rare opportunity.”

“Respect that. Let that be your grounding,” he added.

Chance presented Duke a shot at a career he hadn’t fully considered, and it ended up yielding life-altering results. That fact is not lost on him today. “There’s so many talented people out there working really hard,” he told me, “and there are some things that happen that can make things harder or easier [to succeed.]” An introduction. A few opened doors. One opportunity. Another. The support of knowledgeable family and friends. In Duke’s case, none of these were presaged, but each held significant sway over the trajectory of his life. Paired with his abilities as an artist and his work ethic, and the result was a career to be envied. Rather than floundering, as so many emerging artists do, he began to thrive.

Since the end of World War II and the incredible rise of arts programs within the post-secondary education system, many artists have been led to believe that success in the arts primarily depends on a skillful expression of their own unique artistic vision. In this belief, skill and grit are the primary determinants of achievement, both of which may (conveniently) be learned in rigorous (and expensive) higher-ed classrooms and conservatories. And while most reasonable people know this largely to be a fiction (we all know brilliant and skilled people who’ve failed miserably despite their best efforts and total ingrates who’ve risen to positions of power and influence despite their obvious lack of competence), this belief still persists, likely because it is such an attractive one. There is an allure to the idea that a person can surmount whatever obstacles life throws at her through sheer wit and determination. And no wonder, it is an empowering image—and one many Americans are intimately familiar with.

The “American Dream,” as we’ve come to know this concept in the United States, was a term coined by historian James Truslow Adams in 1931. It was conceived to refer to the ideal of “a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.” (The Epic of America, pg. 404) Contained within that ideal, also, was a promise of “opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement.” It was an enticing notion at the time, when so many in the country were beset by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness during the Great Depression. It also happened to be a concept that served double-duty as a call-to-action, a narrative that helped drive citizens’ behavior by incentivizing economic participation. By providing hope where there seemed to be none, the “American Dream” narrative stoked citizens’ internal fires, giving them the psychological courage to keep striving, keep working, and keep buying. In short, it was a kind of glorified sales pitch. And, interestingly enough, it is one that has continued to be used to this day to boost the economy through the sale of countless items, including books, plays, educational products and services, and, more recently, homes.

In the arts, a similar story continues to play out. The “American Dream” narrative—supported by the tech industry’s promise that “It’s never been a better time!”—fosters a sense of confidence in those who hope to pursue creative careers. Art institutions, instructors, branding experts, self-help writers, and others follow suit by singing similar tunes, leveraging that hope (for profit, typically) without honestly divulging the numerous risks and uncertainties creatives will undoubtedly encounter in their careers. (If they do happen to discuss the hardships of a creative career, however, it’s generally part of yet another sales pitch for services or training material that promise to help one overcome said challenges… another way to profit off an individual’s sense of hope.) But ultimately that narrative breaks down in the face of reality. Many hardships cannot simply be overcome by increased focus, refined skill-sets, or a higher level of knowledge. The burden of poverty cannot be wished away. A lack of opportunity cannot be addressed simply through grit. Certification does not guarantee that doors will be opened. In the arts, these realities are so profound that “lucky breaks” have become a part of the industry’s common parlance, a fact that is revealing. That good fortune has become so universally longed for—that artists everywhere ache to be “discovered” by art dealers or collectors who’ll raise them out of poverty to riches and glory—puts the lie to the notion that merit alone determines one’s fate. In a true meritocracy luck would hardly be an advantage. It would be so negligible people would hardly dwell on it. But the truth is, good fortune can mean the difference between sinking or swimming… and so many people find themselves drowning today with no relief in sight.

The promise of America is one of equity and opportunity, but it is a promise that has yet to be fulfilled for many Americans. The arts and other creative fields provide a case study in this, revealing a system wherein the combination of one’s hard work, skill, and determination doesn’t assure favorable outcomes. And because of this dynamic, luck has taken the forefront in the hearts and minds of those striving to become a part of the industry. This, of course, is alarming. It is absurd and reckless to allow one’s life to bank on the hope of an improbable win in a game of chance, and yet so many of us—especially those of us in the arts—allow ourselves to be driven in just such a way. But given the lack of a truly meritocratic system, as well as unfulfilled promises of equable opportunity alongside a racket designed to foster false hope, who can really blame us? The alternative seems much worse: a life devoid of hope. With that outlook, a person would be right to throw up her hands and simply call it quits.

Clearly, something must be done to decrease our own reliance on luck in a way that keeps us hopeful, eager, and willing to put in the hard work necessary for achievement. But we must also address the systemic failures that allow chance such a firm grip on the outcomes we enjoy (or don’t.) So, what can artists do?

One answer would be for more artists to follow the example of Duke Beardsley and meditate on the role of luck in their lives and career development. Not only would that help provide a more honest depiction of the industry in its current state, it would help pinpoint specific areas in need of reform. These areas could then be addressed in a systematic, industry-wide manner.

Another answer may come in the form of advice originally intended to improve one’s own art. “I had a great friend, mentor and teacher in California named Ray Turner, who is maybe one of the finest genre painters in the States today,” Duke told me. “He was always pushing really hard to get a big-picture understanding of what’s essential. He said, ‘Learn the difference between the precious and the essential.’”

“You can spend so much time spinning your wheels on things that ultimately don’t matter, because it’s easy to get caught up in various aspects of this,” he added. “So, learning what’s essential and focusing on what’s essential to you and your art is a very key step.”

If you are someone drawn to the arts, then some deep reflection is in order. In what areas are you spinning your wheels? Do those things ultimately matter to your practice or your career? What components conclusively add up to a good life? Do your dreams restrict you, or do they inspire you towards constructive action? Are accolades essential? Are big payoffs, press, and acclaim? Does a rabid need for clicks, likes, follows, or eyeballs serve your art or life in a meaningful way? What is truly essential for the life you want to lead or the legacy you want to leave behind? How can you adjust your habits, practice, and focus in a way that allows you to move towards these things?

The power of this effort can be seen in the art of Duke Beardsley.

A Duke Beardsley painting is a unique celebration of that which is essential. High contrast figures rendered in monochromatic or duotone color schemes arrest the viewer immediately. Much like venerated icons of previous eras, the deceiving simplicity of each composition helps create a tone imbued with a sense of sacredness. His bold, vibrant pieces declare an appreciation for life, specifically his life—a life firmly rooted in the contemporary rhythms of an urban upbringing and flavored with a deep connection to the land. “[When I was growing up] Denver was really on the verge of breaking out of its longtime cowtown reputation to become this vibrant metropolitan area that it is now, and we had a cattle ranch an hour and ten minutes outside of town, where we spent weekends and holidays,” Duke told me. Once he returned to Colorado after attending ArtCenter College of Design, he wanted the work he produced to express that same unique experience. “I say this with all respect possible, I didn’t want to be dragged into the Charlie Russell, Frederick Remington genre of very literal, very narrative, traditional western art,” he said. “I love those guys. I grew up worshiping them, but [their work] didn’t feel like my time. That’s not the West I experienced on my family’s ranch. It’s not the West I experienced on my friends’ ranches. It’s not the West I experience at all.”

“It seemed like an interesting if not pleasurable challenge to bridge the gap [between those worlds.]”

As a result, Duke’s art became a mechanism of reconciliation. Influenced as much by abstract expressionism and pop art as by traditional western landscapes and narrative illustration, today Duke renders his own experience of the West in a way that is true to himself. It has become a reflection on the developing nature of life and a proud declaration of his own unique place in the shifting story of the West. And it’s easy to see Duke’s work as a proclamation of gratitude, too, a testament of love for the life he’s been able to lead. His art serves as a visual metaphor, as well, revealing not only the hard-scrabble realities of effort and enterprise, but the randomness of life itself, utilizing intuitive brush strokes and texture alongside tight, skillful rendering. Unlike so many artists of the West who seek to depict an accurate image but instead fall prey to idealism or straight-up fiction, Duke Beardsley’s work shows the truth of experience by concentrating on what is fundamental, employing the most basic, impactful principles to carry his message.

And his message seems to be this: the essential aspects of our lives are what give life meaning. Direct your attention towards those things. Appreciate them and hold them dear.

His is a message of rapture for these things, and the metaphysical relationship one has with them. It is also a message that makes no promises and offers few answers, in part because Duke understands the incredible uncertainties we face in life and art. But that is what makes the message a truthful one, because life rarely offers an easy solution, and randomness flavors every moment we breathe. It is no easy thing to face, but that is part and parcel of living a meaningful life.

“There’s a great line by Norman Maclean in A River Runs Through It when he talks about his father, the Presbyterian minister,” Duke told me. It goes, “To him, all good things—trout as well as eternal salvation—came by grace; and grace comes by art; and art does not come easy.”

“It’s true, art doesn’t come easy. It takes a lot of courage and a lot of guts and a lot of luck, especially for emerging artists,” Duke said. “Get ready for some ‘Holy shit, what am I doing?’ because it’s a daily occurrence.”

Uncertainty. Randomness. Luck. These things hold sway over us in ways we cannot control. But if we acknowledge that fact perhaps we’ll free ourselves to focus on those things that are essential, meaningful, and affirming. False hopes might fade, and those who would seek to profit from them would similarly disappear. A life of gratitude and clarity might then be possible, even in this age of distraction.

Grit can help one persevere in the face of bad luck, but it doesn’t necessarily help overcome it. Skill is certainly valuable on the road to achievement, but it certainly doesn’t guarantee success. People can and should advance because of their merit, absolutely, but given the incredible disparities in access and opportunity we see today, this is an ideal that is far from being fulfilled. Nor, in its current form, is it an ideal insulated from the incredible influence of chance. After all, traits such as grit are influenced more by the environment one is randomly exposed to during development than by any deliberate choice made on one’s own part. Plus, valuable skills can only be learned if one has the opportunity to learn them in an atmosphere conducive to learning them in. Personal choice has little to do with whether these things coalesce in one’s own life. They occur, for the most part, through sheer luck and happenstance.

This is not to say people shouldn’t work hard. Nor is it to say hard work shouldn’t be rewarded. No, those who work hard should most definitely benefit from their efforts and contributions, but chance ought not to determine their reward. The risk we run from ignoring the role of luck in our lives is that disparities will continue to grow and social cohesion will continue to fray as whole segments of the population are left to wither in cynicism and despair while society’s “winners” shrug their shoulders in the most patronizing way. Luck must become an important topic of discussion moving forward—especially in the arts, where the difference between “winners” and “losers” can be extreme to the point of absurdity. We may all be swimming in the same sea, but let’s remember, there are those who were lucky enough to have entered the water with the gift of a life preserver, while others never had the opportunity to learn to swim. Do we really want to leave those poor souls to drown?

As someone who has felt the pain of water filling my lungs, the thought of that sort of indifference frightens me.

In a world that allows randomness to be linked so closely to reward, it’s easy to lose sight of those essential things that make life worth living. So many of us become distracted by the scrum, scrambling to the head of a hungry mob to claim our winning lotto ticket (”You can’t win if you don’t play!”), that we forget what’s essential and what’s necessary. We forget what agency we have and thus enslave ourselves to dreams and fantasy. No more. No more.

We do not have a say in when Lady Luck will grace us with her presence. We can prepare ourselves as best we can to take her by the hand when and if she appears, but we have no guarantee she will indeed appear, or when. That gives us little choice but to work to make her influence negligible, by directing our aims and attention towards those most essential aspects of our lives, and by extending a hand to our drowning fellows.

Not only because it is right and just, but because that is what we’d want when we begin to sink—an attentive ally to keep our heads above water.

We should all be so lucky.

Duke Beardsley’s work can be found on his website, Instagram, and Facebook, as well as numerous regional galleries. His work can also be found in a number of notable collections, including Denver Art Museum, Booth Western Art Museum, the Ritz Carlton art collection, Forbes, UMB Banks, and the Whitney Collection.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

Become a Patron Without Spending a Dime. Learn More Here.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.