Asceticism is a practice with a long history the world over. Typically, the practice consists of some form of abstinence, frugality, and retreat—or a combination of all three—for a specific spiritual purpose. Some ascetics pursue redemption, others seek communion with their deity of choice, and still others remove themselves from the distractions of the world to discover an ephemeral thing called “truth.” Siddhartha Gautama, later known as The Buddha, practiced asceticism for a time, as did Muhammad, John the Baptist, and Jesus of Nazareth. Yogis, Jains, Sufis, the Desert Fathers and various monastic orders from different religious traditions have all been known to practice asceticism as well.

To this day asceticism remains an attractive pursuit. Contrary to its historical spirit, however, modern asceticism has become something of a booming niche industry in and of itself. Retreat centers pull in thousands of eager visitors each year, each hoping to achieve some form of peace, relaxation, enlightenment or healing to the tune of several hundred (or thousand) dollars a pop. Cell phones and electronics are generally banned. Simple food is generally served. And in some centers, a strict code of silence is uniformly imposed. It is not unusual for contact with the outside world to be restricted. Nor is it uncommon to find these centers in mostly rural, or extremely isolated settings, away from the buzz and the convenience of metropolitan life. You pay, in other words, to remove yourself from the diversions of the world, to sit in silence and without entertainment. (To me the profiteering take on the ascetic tradition betrays the original intent, but what do I know? I’m just a guy who believes crystals are interesting physical structures not conduits for an undefined cosmic source of healing energy. So, maybe I’m missing something.)

Regardless, modern asceticism has largely kept to its individualistic bent. It is up to the individual to choose the time, place, and conditions of her ascetic practice—to choose her level of commitment based off her intentions and tolerance for discomfort. (There are certain circumstances, particularly in the case of radical religious sects or cults, where individuals are given no option but to pursue an ascetic lifestyle. Thankfully, as we become more committed to the ideals of universal human rights, these cases are dwindling as more people become free to guide the trajectory of their own lives.) Today, however, that story has shifted slightly because of COVID-19. Social distancing and shutdown restrictions that began in the U.S. in March of 2020 have pushed many Americans into an informal state of retreat. The luckiest were equipped to work from home, surrounded by family, able to socialize with a protected “pod” of similarly isolated friends. For others, the experience quickly turned into a nightmare. Forced to adopt a lifestyle of austerity due to economic hardships, and isolated from meaningful relationships, some Americans have endured the pandemic in a state of constant suffering. Contrary to the respite New Age retreats insist their own participants enjoy, these isolated individuals have experienced (in some cases for over a year and counting) an endless bout of distress due to imposed asceticism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Declining mental and emotional health has never been more of a concern nationwide, and solitude seems to be the strongest link in the causal chain leading towards that particular deterioration. Loneliness is on the rise—and along with it depression, anxiety, and acrimony.

While some ascetic traditions believe suffering is important to the overall practice, most do not treat it as a primary (or even necessary) process to achieve one’s aims. The purpose of the practice is not to suffer. Generally, the purpose is to unearth realizations about the conditions of life and one’s role in it. From this one may derive clarity and perspective. The stripping away of the trappings and complications of life is a revelatory act, one which leads to something one might call, in the abstract, “enlightenment.” This is why Jesus walked into the desert and remained there for forty days and forty nights. This is why Siddhartha Gautama left his life of sheltered privilege and donned monk’s robes in the wilderness. This is also why Ingmar Bergman sought refuge in a cabin on the island of Faro, and why Georgia O’Keeffe worked from a studio in New Mexico. Solitude, in each case, proved illuminating.

So why is it that solitude in one context is sought for its benefits, and responsible for immense suffering in another? And what can be done about that? An inquiry into these differences seems needed.

Perhaps a place to start might be to observe those who practice ascetic-like behaviors in order to demarcate the experience. From there, strategies could be extrapolated for the benefit of those who’ve been thrust into a state of suffering due to their seclusion. Interestingly enough, people who lead creative lives would appear to be of particular value for just this type of investigation. Since many creative types work (and sometimes live) in relative solitude, it would seem the insights provided by artists, writers, thinkers, and those in related creative fields would provide useful data points here.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, the New York Times identified the occupation of Fine Artist second only to Loggers as being the least likely at risk for coming in contact with the virus—which is another way of saying least likely to encounter other people,” S.M. Chavez, a painter based out of New Mexico told me.

To this we could probably add, with a degree of confidence, ‘least likely to suffer negative effects from pandemic-related isolation.’ But is that simply the function of a unique personality-type or are there lessons we can glean here that would help the wider population?

What exactly is the creative relationship with solitude?

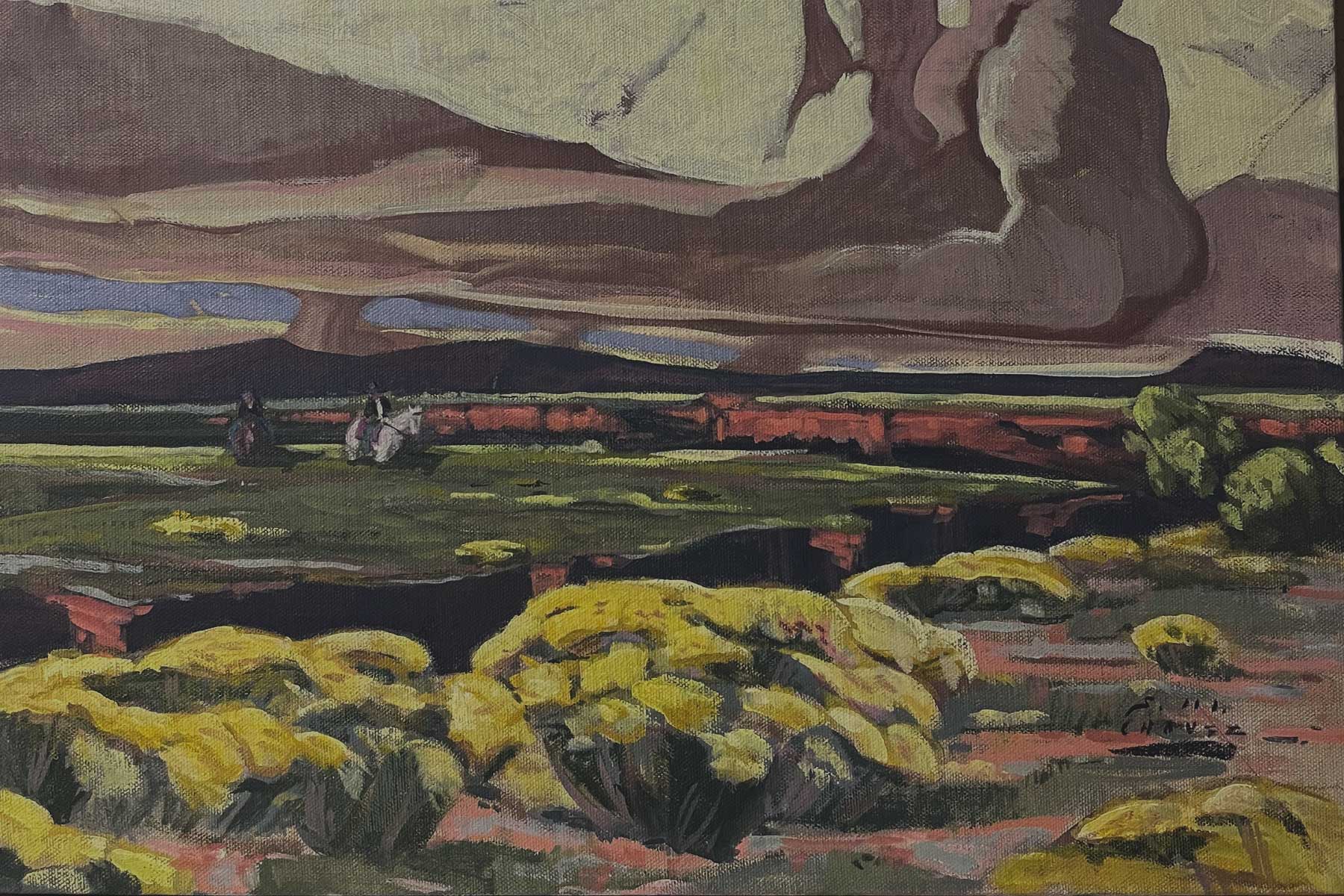

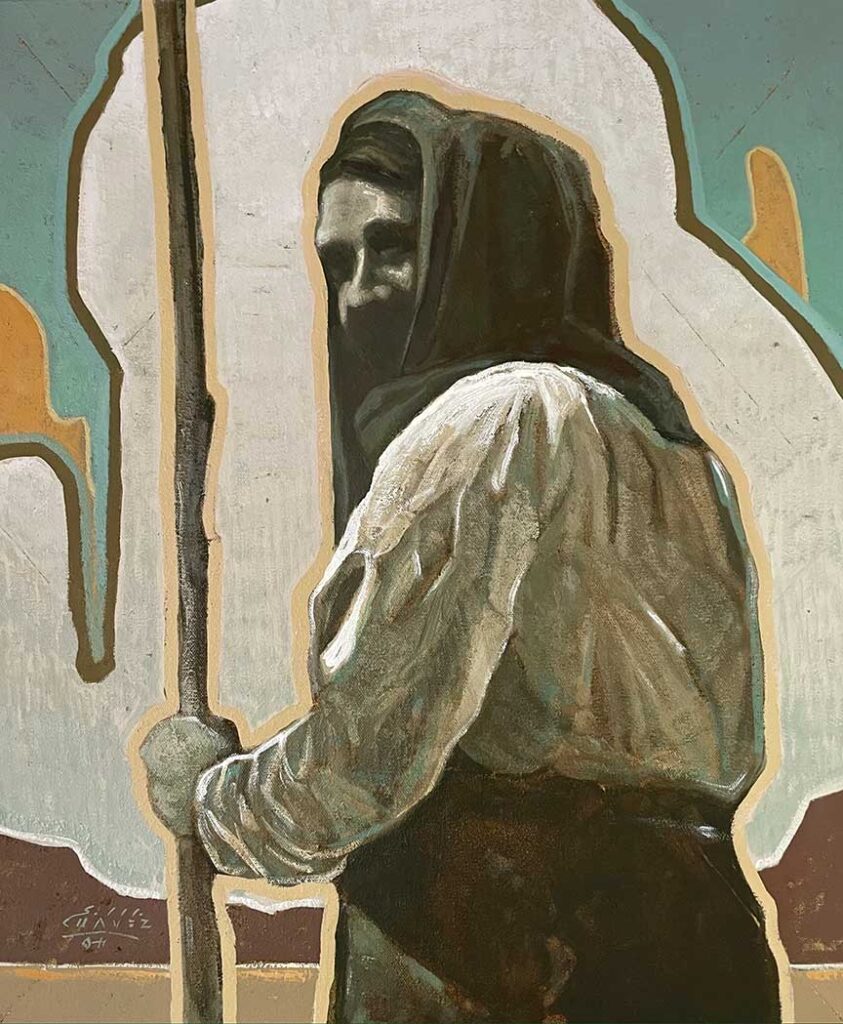

Sean Michael Chavez (also known as S.M. Chavez) is an oil painter known for work that is sophisticated and subtle in its approach to color and bold in design. His is work that has earned him invitations to prestigious annual shows, including Small Works, Great Wonders at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, the Coors Western Art Show in Denver, and The Couse Foundation’s 2022 Gala and Art Auction in Taos, New Mexico, whose participants include the likes of Thomas Blackshear II, Glenn Dean, Logan Maxwell Hagege, Jerry Jordan, Mark Maggiori and Ed Mell. And it is work that has clearly hit a nerve with collectors as well. During the inaugural weekend of his first exhibition at Acosta Strong Fine Art in Santa Fe, his pieces sold out, proof positive that he has achieved sought-after status.

For the uninitiated these accomplishments might easily be attributed to innate talent or an uncanny relationship between the artist and the tools of his trade, but to those who’ve spent time in front of a blank canvas they represent something else entirely. They are the result of a high level of focus and commitment. They represent countless hours spent alone developing a craft, learning, failing, rising up off the floor of defeat and despair, and persisting. They represent quiet effort rarely seen and hardly celebrated, a years-long journey marked by solitary footprints leading towards an interminable horizon.

“I have always been artistic,” S.M. Chavez admitted to me. “[I’ve been] drawing and painting as far back as I can remember. Much of what I have learned has been by wearing down pencils and emptying tubes of pigment.”

It is a story many artists are familiar with, the inescapable urge and obsessive commitment to the brush, pen, or pencil. Progress, in the artistic realm, can be weighed by the detritus left in the wake of one’s pilgrimage, and measured by the lengths one will go to improve. In S.M. Chavez’s case that meant countless pencil nubs and thousands of miles. After graduating from Southwest University of Visual Arts, he left his home state of New Mexico for California and Massachusetts. Both “migrations,” as he put it, were made possible through sales of his artwork from self-promoted exhibitions. But his travels, and his artistic pursuit, didn’t stop there. “Going to museums, including the MFA Boston, NY Met, NY Guggenheim, The Louvre, Musée d’Orsay, Centre Pompidou and others, has been absolutely invaluable in regards to making paintings,” he told me. “Absolutely nothing beats seeing a work firsthand in terms of scale, context, technique and presence.”

A romantic mind may perceive similarities between this self-directed artistic journey and the quests of the errant knight of medieval legend or the wandering monk of eastern lore. Dreamy vistas pass through the mind’s eye. Adventures. Heartbreak. Visions of idealistic withdrawal sustained by an ethereal spirit or muse. In previous centuries this kind of thinking is precisely what laid the groundwork for the trope we know today as the reclusive creative genius. During the subsequent rise of bohemianism during the 19th century, that same trope gained popularity and power (particularly in the West) such that even in the 21st century it still proves spellbinding. But as we begin to consider the relationship between creativity and solitude, how much faith should we put in this romanticized narrative? Should we believe that progress only emerges from utter isolation, as the trope of the reclusive creative genius suggests? Or is there some nuance we’re missing?

“Science has confirmed that time for solitary reflection truly feeds the creative mind,” wrote Scott Barry Kaufman and Carolyn Gregoire in their book Wired to Create: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind (p.48) “The act of creating requires us to find time to ourselves and slow down enough to hear our own ideas—both the good and the bad ones. Some degree of isolation is required in order to do creative work, because the artist is constantly working through ideas or projects in his mind—and these ideas need space to be developed.”

“My feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required,” the prolific writer and biochemist Isaac Asimov pointed out in his essay On Creativity. “The creative person is, in any case, continually working at it. His mind is shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it… The presence of others can only inhibit this process, since creation is embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display.” But this does not mean solitude is the be-all and end-all. Collaboration and communication can be, Asimov goes on to say, just as vital a part of the creative process. Peoples’ mental processes are not the same, he notes, and the combination of unique perspectives may yield insights which would have been difficult for individuals to come by themselves. “If one person mentions the unusual combination of A-B and another the unusual combination A-C, it may well be that the combination A-B-C, which neither has thought of separately, may yield an answer,” Asimov wrote.

So, solitude is an important part of the equation when it comes to creativity, but a complete withdrawal from the world is not. In fact, pure isolation may inhibit the creative process because it removes alternative perspectives from the equation, making it less likely important creative sparks get lit at all. This is a common issue many creatives run into, especially among those who work from the privacy of a sequestered studio. It is also one S.M. Chavez has struggled with in his own day-to-day practice. “It is not like I am never in contact with others, but there can literally be many days at a time when I don’t have contact with anyone to provide valuable feedback on what I am working on or towards,” he told me. “There is a lot of time for thinking, and that can often lead to questioning anything and everything.”

Despite the requirement for solitude, connection is still an important part of the creative process. So, while there may be a grain of truth in the trope of the reclusive creative genius, the characterization is clearly an exaggeration. A balance of solitude and interaction is necessary to produce creative breakthroughs, or to make constructive insights. The interplay is a dynamic and cyclical one, where each state of being necessarily follows and feeds into the other. If the scales are weighted too much in one direction it throws the whole endeavor off-kilter, skewing the results. Input and interaction serve as counterbalances, helping to properly align creative output. In fact, anything that isn’t the result of just such an equilibrium would be like the proverbial tree in the woods. Does it make a sound? Does it even matter? Removed from its broader contextualization and interrelatedness, I would hazard to guess that no, it does not.

But wait! If this is all true it would suggest those who practice ascetic-like forms of retreat, such as artists, might not benefit from prolonged forms of isolation. What lessons could possibly be derived from their experience if that is the case? How can this discussion on the relationship between solitude and creativity really benefit those suffering due of pandemic-related isolation if it turns out it those best equipped to deal with it may be hampered by it as well?

While these are valid concerns, we may want to reframe them. As we’ve already established, solitude is a necessary component in the creative process—it is not the enemy here. Neither is solitude something to be eschewed outside the creative domain. In fact, according to psychologist D.W. Winnicott, one’s capacity to endure solitude “is one of the most important signs of maturity in emotional development.” “The relationship of the individual to his or her internal objects, along with confidence in regard to internal relationships, provides of itself a sufficiency of living, so that temporarily he or she is able to rest contented even in the absence of external objects and stimuli,” he wrote in The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development (p.31).

If one is incapable or unwilling to tolerate solitude in any shape or form, it could indicate some psychological weakness requiring intervention. “The very idea of solitude may evoke deep childhood fears of abandonment and neglect, and cause some people to rush toward connectedness,” wrote psychologist Ester Buchholz in her article The Call of Solitude. A fear of solitude may come from societal pressures, as well, she noted. This can be the result of modern trends like hyper-productivity and ultra-efficiency, both of which demand constant interconnectivity, speed, and snappy decision-making. These pressures contribute to the fear of solitude by creating environments antithetical to reflection and prudence, and by making each moment alone seem like a cost to the individual’s livelihood and future. This, Bucholze points out, is a terrible mistake. “Our error is in presuming that aloneness and attachment are either/or conditions,” she wrote. “They are at odds only when they are pitted against each other.”

Solitude need not be feared. It is useful, and the ability to endure it is one mark of a confident, mature individual. Therefore, instead of avoiding or dreading moments alone, we should use them as an opportunity for growth. Solitude is a perfect vehicle for contemplation, providing time to unravel problems and to process important experiences. This is effectively the work artists do in their studios. They reconcile experience through paint, pigment, clay, canvas, and paper, working out their thoughts and feelings through the medium of their choice. It’s not perfect or easy or idealistic—it’s difficult work! But still, artists make the effort because they understand its value. And that might be one of the most important takeaways for those facing solitude, voluntary or otherwise: how one thinks about and proceeds to take advantage of time alone matters. To rephrase the iconic Henry Ford quote, whether you think solitude is profitable, or you think it’s a waste—you’re right. To this writer, it’s better to think the former. It’s time to reframe and reclaim what time alone can offer us.

Now that we’ve firmly established the value of solitude and how one ought to take advantage of it, we must address the real challenge of managing connection in a way that complements the insight and progress one has made on one’s own. Depending on the circumstances one finds oneself in, this return out of a state of retreat may take wildly different shapes. For some, it may look like a typical day, surrounded by collaborative colleagues whose interests are aligned with the individual in such a way that integration isn’t much of a problem. For others, especially during this time of pandemic-related separation, opportunities to engage with good-faith associates may be extremely limited. In these more difficult cases, creative solutions need to be found. Luckily, for those who are willing to be open-minded, there are collaborative, contextualizing opportunities all around us. Cultural products can be excellent mechanisms for this kind of thing. In the arts that means studying, learning from, and engaging with the work of other artists—and not simply artists whose work fits one’s own preferences, but artists of all disciplines. While an artist may be isolated such that she cannot speak or interact with another artist, most are lucky enough (particularly in the U.S.) to have access, in one form or another, to the work of numerous other creative people. That means she has the opportunity—in the lingua franca of phenomenology—to enter into “dialog” with the intellectual fruits of countless other individuals. Interestingly enough, this collaborative “hack” isn’t a new idea. It is an accepted—even encouraged—form of learning, development, and growth. And artists like S.M. Chavez have employed it to create work rooted in tradition, culture, and history in a way that is entirely unique and in a voice all their own.

Creativity is typically defined as an ability to produce novel combinations of ideas in ways that are useful. (In the arts, ‘useful’ generally means the work is able to alter one’s internal milieu in some meaningful way. It does not mean the work can be taken off the wall and used as kindling, or as a hammer, or as a table cloth.) The creative act, although commonly celebrated as coming from one-of-a-kind minds, necessarily requires an environment teeming with a diverse array of concepts out of which novel products can be crafted. It is collaborative and communal, then, with manifold ideas forming a kind of connective structure out of which new structures emerge. In that sense an S.M. Chavez painting is an exemplar of the creative act. Each contains allusions to the past, to particular traditions and ways of life, but each remains a bold, modern artifact in its own right. The developing stories of the Southwest, of its people, its culture, and its landscape are laid out in confident marks and captivating midtones, giving the impression one has entered a dream-space from which new wisdom will emerge. It alludes to its foundations, showing you the underlying substance out of which fresh creative tissue has been formed. Old and new are merged in contemplative compositions, skillfully leading the viewer inward, then outward, and beyond.

This is what it means to converse and collaborate with others through the artifacts they leave behind, using one’s own insight to add to the overall dialog. It is an age-old practice, particularly in the arts, where interaction, adaptation, and integration have traditionally been the name of the game (amongst those trying to advance the field, anyway). But, surprisingly, not everyone in the arts industry understands this, and the result isn’t so pretty.

To an outsider, dogmatism, elitism, and general snobbery are emblematic of the arts; it is the consequence of one’s participation. (i.e. the more training you receive in the arts, the snootier you become.) But really these things are manifestations of an imbalance resulting from an inability (or refusal) to integrate one’s knowledge into a wider contextual fabric. By this reading, those who suffer (Yes, suffer. These are miserable people we are referring to here.) from elitist tendencies are like ascetics who’ve retreated from the world and refuse to return. Tensions emerge because the collaborative process is stymied, halting the overall creative one, and so people retreat to their own solitary corners to lash out in fear and confusion. As a result, the environment degrades, leading to an increase in overall suffering. But wiser minds recognize this for what it is and commit to the work of placing themselves within the context of an interrelated whole, knowing it serves to act as a stabilizing, creative force. S.M. Chavez is of such a mind, understanding that his connection to and dialog with diverse creative products has a positive influence in his life and work, and in the lives of others.

“There is no inferior art. Abstract art, conceptual art, figurative art, landscape art, outsider art, enthusiast art, they all have their place and their purpose — to add value to our lives,” he told me. “I playfully imagine a museum where contemporary artists of all disciplines, styles, techniques and subjects would gather to learn, support and grow from each other.”

In lieu of such a social, collaborative environment, S.M. Chavez encourages artists to pursue a similar objective in a self-directed way. “Compare your work to the masters within your field and find something about or within your own artwork that sets you apart,” he told me. “Accentuate that uniqueness and then evaluate it. If you have fallen in love, do it again. If you are dissatisfied, repeat the process, but try something new.”

“Once you have fallen in love, don’t be afraid of it. Feed it. Don’t talk, show,” he added.

The work artists do in solitude reveals that we are connected in ways that go beyond the face to face. Interaction and communication do not cease when we no longer feel the breeze of another’s breath or their spittle on our cheek. Our relationships are deeper than that. They delve beneath the superficial into the realm of the abstract where ideas, emotions, hopes, dreams, and fears reside. And here there is much work to be done, many things to discover, and many avenues for growth. Solitude is not a place to be feared but a place we should actively, joyfully, explore. Time alone is not time wasted if one understands its value, and time alone isn’t necessarily time lost in separation from others, especially if one maintains a creative, collaborative mindset. We can still relate to those around us, even if we are the only ones in the room.

Solitude may indeed be difficult for some, but given the boundless opportunities for connection it need not be painful. Undoubtedly, time spent in solitude can be incredibly rewarding, not just for the individual but for the community. It can add incredible value to the wider, interconnected web we all benefit from. I would encourage readers to strive and produce such dividends. Your purposeful use of precious time may one day serve to lift another. “Perhaps my work may one day inspire the next Dixion, the next Dunton, Couse or Sharp,” S.M. Chavez told me. “If that was my role, it would have been well worth living.”

Indeed, it would have been time well spent—but never alone.

“I am grateful,” he added. “I am grateful to the collectors, curators, gallerists, writers, publishers, followers and anyone that continues to find interest in my work. It is because of those around me that I am able to paint with such increasing focus and with such a full heart. I am indebted and without words. My paints speak for me now and they honor those that have played a part in giving me this gift.”

S.M. Chavez’s work can be found at Acosta Strong Fine Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, online at his website, and on Instagram.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist and Conversations series were conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

Become a Patron Without Spending a Dime. Learn More Here.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article or Conversation—or to nominate someone —please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.