One easy-to-find nugget of wisdom making the rounds on the Internet these days reads:

“The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.”

― Aristotle

But while the words make for an insightful expression, they do not, in fact, belong to Aristotle. They rightfully belong to the historian William James Durant, having been lifted from the pages of his 1926 book, The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater Philosophers. (The exact words can be found on p.71 of the 1962 Simon & Schuster reprint, in case you were wondering.) Although Durant’s words do not misrepresent the famed philosopher’s conclusions, his brief summarization simplifies nuanced arguments the ancient philosopher originally made in ways he likely would reject (all the more reason to rectify the issue of attribution here). This is, after all, the man credited with the earliest study of formal logic, a practice founded on the use of extreme precision in the evaluation of arguments.

Interestingly enough, however, the specific reasons why we (wrongly) attribute the words to Aristotle provide evidence in support of one of the philosopher’s conclusions about our nature, and, by extension, our undertakings (including those within the realm of art). Humans, according to Aristotle, are naturally inclined for imitation, representation, or mimicry, a phenomenon he referred to as mimesis (μίμησις). It was, in his opinion, among the most powerful reasons humankind came to rise above all other creatures. “From childhood men have an instinct for representation, and in this respect, differs from the other animals that he is far more imitative and learns his first lessons by representing things.” (Aristotle, Poetics, I, 1448b) A child learns to speak through mimicry. An individual learns a trade by imitating those who came prior. Even poetry and music, Aristotle argued, developed out of an instinct to imitate rhythms found in the living world. Likenesses, or representations, are inherently pleasing to us, he believed, because we learn and infer from them. The impulse for imitation, in other words, is what drives us to grow and develop.

The products of this imitative, representational instinct were later given a name by biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene. By taking the appropriate Greek root and shortening it to a monosyllable, he proposed using the term meme to refer to a “unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation.” (p.192) “Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperm or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.” (p.192) In short, the instinct for mimesis Aristotle explored in his Poetics, provides the drive to produce units of imitation Dawkins called memes.

In popular culture today, memes are almost universally known as lighthearted images or video clips shared via social media. While Dawkins intended the term to refer to cultural units outside the realm of Twitter and Facebook (social media platforms did not exist when he coined the term), the underlying instinct remains true to the original. Memes in the Internet ecosystem emerge out of the very same impulse to reproduce and imitate that Aristotle wrote about, and they fulfill this impulse by employing unique units of cultural transmission in the form of images, GIFs, and short videos. The reason why so many believe the aforementioned quote comes from Aristotle originates with this same mimetic instinct as well. At one time someone misquoted the philosopher and, thanks to our inherent inclination for imitation, others followed suit. Today, in classic mimetic fashion, it has taken the form of something that is easy to thoughtlessly upload, post, tweet, and DM. To take it full circle, while the quote does not belong to Aristotle the underlying rationale for its spread still reveals the truth of Aristotle’s insights on human nature. How’s that for an interesting twist?

But what all of this also reveals is an inherent weakness we all possess. Namely, our instinct to favor what I’ll call superficiality over substance, an urge to be satisfied with mimicry, representation, or fiat. It is this tendency that leaves us stranded in the one-dimensional, oblivious to deeper meaning. Our surface-layer reflections are what blind us to nuance, gradation, and profundity. We concern ourselves, unfortunately, with the “outward appearance of things,” as William Durant put it, never seeing their “inward significance.” And that is precisely the problem art is solving for. The aim of art, the historian believed, is to help us penetrate exteriority.

That means art carries with it a particular burden, a responsibility to speak with the kind of depth we are not altogether comfortable with. To help us see is certainly a high purpose. Indeed, it is a goal few can meaningfully achieve. Still, there are some who make great strides in this direction, including select individuals who reside here in the regional West. One case in point is Blanche Guernsey, a Gillette-based painter whose work depicts precisely what Durant was writing about. Hers is work that takes us past the mundane and into the vast interior landscape of thought and memory, challenging viewers’ instincts for the superficial as they are led inward towards things more substantial.

“Memories are powerful, intangible, ethereal,” Blanche’s artist statement reads. “So often, these memories—these strange instances—are triggered by objects that can take us back to a specific time or place. My work examines these objects in such a way that the viewer might share a glimpse of their significance.”

As a self-described introvert, Blanche Guernsey found art to be a useful—and meaningful—way to process and reveal the unique experience of her own life and surroundings. It was that way from the time she was a youth. “Art class in school was the only place that I ever felt welcomed and [like] I belonged,” she told me. “When I was working on projects my mind was always transported into that ‘zone’ where it felt like the class was only minutes long, and I dreaded having to clean up to get to the next class. There was never anything else for me. I knew from an early age that I would be involved in the arts in some form.”

The body of work she came to develop over the years materialized out of this deep connection to art in a reflective way, with paint becoming a vehicle for her unique form of contemplation. Her recursive methodology then folded in upon itself, resulting in a focus on the exploration of remembrance and nostalgia. It was a vector, she discovered, that held power, and she wanted to share it with those around her.

“I hope to connect generations while reminding people of what was,” Blanche told me, “to inspire and bring magic to the memories we all hold on to.”

Today, the mother of five appears to have succeeded in that regard, having established a presence and a broad base of support that seem to contradict her claims to an introverted nature. (At the very least, it is the kind of diffusion those who share her inclination would generally find uncomfortable. Being the center of so much attention is not something many introverts would envy.) Her work has won awards and been featured in Livability Magazine and W Magazine for Wyoming. It has shown at numerous regional galleries, including those in Gillette, Casper, Sheridan, and Rapid City, South Dakota. And her reach continues to broaden. It is clear that Blanche has struck a resonant note with art-lovers and collectors in the West.

Considering she never received formal training, it is easy to understand this as being quite the accomplishment. Indeed, it speaks to a level of persistence and love that few, professional or otherwise, could claim. “I practice, I observe, I take workshops, I research, I share, I read,” Blanche told me. “I work [all this] into my daily routine.” It was a methodology that served her well.

But the outlook wasn’t always so rosy. Like many artists—particularly those who lack the privileged support systems found in well-connected art programs—gaining ground proved to be a struggle. But she persevered, reframing each obstacle into a learning opportunity and a way to give energy to her practice. “With every rejection—and, man oh man, there [were] so many rejections—I would think that I need to do better, push myself more, learn something new,” Blanche told me. “Rejection is always hard, but I used that as fuel more than anything.”

“I have learned that in order to grow you need to fail, to push yourself, to go outside your comfort zone,” she added.

But what—besides drive—accounts for her accomplishment in the arts?

Perhaps it has something to do with the intention behind her paintings, that purposeful resolution to reveal that which goes beyond the superficial. Perhaps it is in her ability to reveal deeper meaning, as though her subjects were translucent drapes hanging at the edge of one’s consciousness. Put another way, perhaps collectors respond to Blanche’s work because her representations reveal the “inward significance” William Durant was referring to in his mimetic, misattributed quote.

Perhaps it’s because she does exactly what artists are supposed to do: she helps us to see.

Among the numerous problems the art industry faces, a lack of clarity reigns supreme. There is a veritable lack of meaningful data available to those who wish to gain entry, or even to many veterans who’ve long struggled to maintain gainful employment. Valuation, assessment, approval, and access to support are mechanisms necessary for success in any market, and are generally available to all those hoping to join the competitive lists, assuming they’ve met clear-cut, agreed-upon criteria. But in the art market this is largely not the case. These mechanisms are withheld with a notable lack of transparency, hidden behind two-way glass and secured by a lock whose keys only a select few possess. Even the criteria by which one might earn entry are concealed beneath a screen of obfuscation. This is what economists call a black box, an opaque environment that resists scrutiny. Not surprisingly, this phenomenon has been detrimental to the market, particularly as it pertains to confidence and faith in the system.

“Who in the art market do I trust?” Nanne Dekking, the former top salesman at Sotheby’s and current CEO of the blockchain art registry Artory, once lamented in an interview. “They don’t want to trust anyone.” (Money Reimagined podcast, Ep. 16, Feb 19, 2021)

Opacity obscures bad behavior and breeds mistrust. To illustrate: If artists do not know how galleries assess, manage, and trade, how do they know galleries have their best interests in mind? If collectors do not know specifically how art is valued—or if pricing mechanisms are deliberately obscured—how do they know they are not being had? If there is a lack of transparency between galleries and artists, what’s to stop them from working at cross purposes? If assessment is achieved using ill-defined, subjective protocols, how are pricing schemes ethically justified? How do new voices find their footing if entrenched gatekeepers refuse to cede territory and jealously control entry? How do outsiders pierce the veil of elitism? Without trust and clarity, these questions will never be answered to anyone’s satisfaction.

But let’s move away from generalizations about the art market and enter the world of systems theory momentarily, so we can better understand broad problems inherent to opaque, concentrated (or centralized) structures. This will help us clarify why reform is needed in the art industry, and illustrate how deep reflection and transparency can get us there.

Imagine a centralized computer database. This database is touted as being efficient and secure. It purportedly operates using a well-defined structure which is supposed to make its use economical and fair to all. Users cannot access the structure to verify whether this is indeed true, but the hosts of the database assure them that doesn’t matter. Users can only trust that the hosts are honest, which they do, because the hosts continually remind users of their expertise and professionalism. To even think about questioning the hosts’ integrity would be a grave insult, so users go ahead and use the database because it seems like a good idea and there aren’t any viable alternatives they know of.

Now, the users of our database depend considerably on the availability of the information contained within it. Perhaps it holds financial, court, and medical records that users require quick and easy access to. Perhaps the database is host to a small company’s ecommerce store, or it holds crucial client contact information. Maybe a small township stores important property records there as well. In other words, our database contains information that is critical to the lives of users.

Like a typical centralized database, ours has a special user account for systems administration. This account we will call, using computing parlance, the “superuser.” This superuser is essential for the functioning of our centralized database, because it uses its special access privileges to perform maintenance tasks, manage infrastructure, and resolve any issues that crop up. Sounds perfectly acceptable, right?

But now imagine our superuser is compromised. Maybe the superuser makes a terrible mistake, or maybe an outsider applies pressure and directs the superuser to carry out malicious actions against certain database users. Maybe the superuser is biased and decides to revise the system to favor certain users over others, giving them an unfair advantage. Or maybe some interloper takes control of the superuser account and wreaks havoc on the database. The convenience of having centralized control, we now see, actually turns out to be an immense vulnerability. If our database did, in fact, contain information that was critical to users’ lives, having an imperiled superuser would put those lives in jeopardy. Since our database also happens to be a black box environment (users have no way of verifying the legitimacy of its internal structure) that means users would have few, if any, means for redress if something went awry. They might not even know they were being harmed until it was too late!

Why would anybody be satisfied with such a system?

Technologists have long been concerned with these exact vulnerabilities. Today, in the computing world, it is being solved in unique ways by decentralizing structures and adding layers of transparency to the protocols that operate within them. The blockchain is a perfect example of this effort, and the result is a system that is so robust it is all but impervious to malicious attacks. That should make us think about the design of other systems in our lives, especially those that have an outsized impact on our day-to-day, including markets.

The lesson here? Transparency and clarity improves systems, and opaque centralization makes them vulnerable. So, we should take very special care when it comes black box environments. Since we cannot see what they contain, how can we know they contain anything of substance? How do we know the black box in front of us will produce results that are efficacious and fair?

We don’t.

Those of us in the art market must seriously consider questions of structural integrity if we wish for it to operate like any other free, open, and efficient market. Otherwise we’re only fooling ourselves, perpetuating superficial falsehoods like those people who thoughtlessly share memes with misattributed quotes. For too long we’ve been the victims of our own misguided instincts, senselessly maintaining the status quo because it exists and because others do as well. Instead, we must crack open the black box so we can find deeper truths, and we must bring those truths into the light of conscious action. We must learn to use our penetrating gaze to breach the dark veil, or we will never find truth, build trust, or achieve resolution.

Let us shift our gaze, so we might find deeper significance. But how do we begin?

Perhaps by reflecting on art itself.

When novices think about representational art, many make the mistake of assuming quality is somehow tied to realism. To their minds, visual art which is near-photographic is superior because of the technical skill required to render subjects with such a high degree of precision. To them, it is a matter of “respect” and technical know-how. But this is a terribly misguided approach to any form of art, particularly representational art, because it traps the conversation in the one-dimensional. While we may indeed find pleasure in imitation, as Aristotle believed, there is a notable lack of substance to be found in sheer mimicry. Art must speak to something broader, deeper, and more profound than that, otherwise why bother? In this digital era, representation can be achieved far more efficiently by other means, so it isn’t really clear what hyper-realism achieves except for a kind of chest-pounding showmanship. Do we really want to reduce representational painting to a contest of mere accuracy, using photographs as its final measure? That’s clearly absurd. Art is much more than an imitative veneer.

Superficial philosophies about art significantly restrict the possibilities of art-making, especially once those philosophies make their natural progression from creation to commerce. Industries reflect the principles of those who belong to them, regardless of how misguided they may be. So, what would happen in an art industry that began to value superficiality over depth? Well, it would look very similar to a black box. A restrictive, arbitrary elitism would take hold, and an obligatory adherence to the norm would become the price of admission. Superusers would tweak the system to further their own ends. Trust would fade.

I, for one, find that unacceptable.

To counter this development, we must learn to look below the surface-level, and one way to do that is to pay attention to those who have something to say about the way we humans think, perceive, and make meaning—to pay attention to those creative voices who teach us to see.

Blanche Guernsey is one such creative voice. The lens by which she explores the artifacts of life serves to penetrate the boundaries of the representational and reveal one’s own inner depths. She does this, to a large degree, by using a reflective methodology that places the viewer into the role of viewed, where one is able to observe oneself as though looking at a revealing snapshot.

This seems appropriate given the fact that vintage film cameras are the focus of one of Blanche’s extensive series of paintings. These, to my mind, are powerfully meta: images featuring the mechanisms by which images are captured. Plus, to add to their reflective energy, some of her cameras are framed in a way that their lenses point straight off the canvas and directly towards the viewer, transforming them into the subject. It is a forceful redirection of perspective, one that shifts the viewing relationship from one of mere passive observation to an active form of participation. It is philosophy in pigment, a conversation with the intent to shift subjective milieu, a way to expose one’s own internal structural makeup. True, there is a vulnerability to be found there, in that sudden shift to becoming the one under scrutiny. Just as one might flinch when in real life a photograph is taken without preparation or consent, these paintings impose a sort of self-consciousness on those who stand in front of them. But that is where the strength of the work lies, because it is only through these uncomfortable moments of exposure and revelation where true insight occurs. It is in this experience, too, where the power and purpose of art as a dynamic force upon our lives is truly realized and felt—deeply—by the viewer.

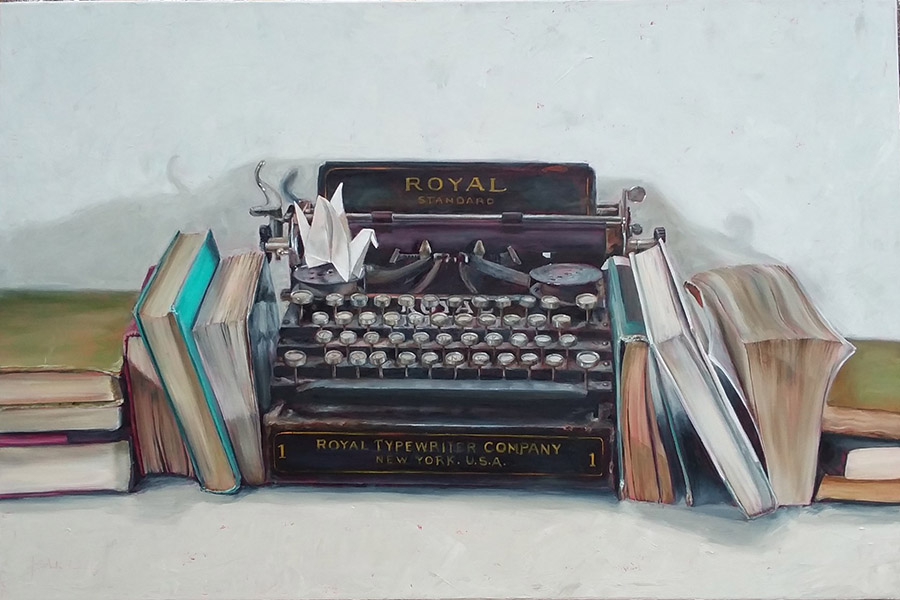

Blanche’s other subjects are equally potent in their rendering. The sheen of reflected light on the keys of a typewriter, the translucent glow of glass, the burnished frame of a classic child’s toy—the play of light and illumination transform each subject into lyrical metaphors, a kind of gentle push towards contemplation and awareness. Hers is a focus on examination, illumination, and the articulation of illusory, internal truths, a focus which fundamentally goes beyond simple mimesis into realms of greater import. In the words of William Durant, they reveal “inward significance,” the greatest achievement an artist could aim for in her work.

We would be wise to absorb the lessons of Blanche Guernsey’s purposeful approach to art, and let it instruct us in how to examine the numerous artifacts embedded in our lives. Let it lead us towards more meaningful ends. Whether we want to further our understanding and refine our own perceptions, or work to reform the grand structures of society, these insights will serve us well, because in the end, what little satisfaction we may have felt at the superficial level will be quickly be eclipsed by the substance we discover when we seek clarity and depth. Aristotle may have believed we all possessed an impulse for imitation, but this was just the starting point on the road to discovery, growth, and development. We owe it to ourselves to seek out and reveal those things that lay hidden to us. We owe it to those around us to lift the veil on those hidden structures which affect all of our lives, so that we might see the truth of their design and work to build something better suited to the interests of all, something that engenders trust, cooperation, and beauty.

That is the power of deep reflection.

That is the aim of art.

Blanche Guernsey’s work can be found on her website, Instagram, and Facebook. It can also be found in various regional galleries, including AVA in Gillette, WY, SAGE in Sheridan, WY, Scarlow’s Gallery in Casper, WY, and

the DAHL in Rapid City, SD.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist and Conversations series were conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

Become a Patron Without Spending a Dime. Learn More Here.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article or Conversation—or to nominate someone —please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.