On January 20th, 1600 Giordano Bruno, an Italian cosmologist and mathematician, was declared a heretic and sentenced to death. He was to be stripped, gagged to prevent “wicked words” from escaping his mouth, hung upside down, and burned at the stake. Far from being cowed, Bruno showed nothing but contempt for those who sat in judgment of him. “Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it,” he said as he made threatening gestures towards the assembled cardinals who made up the court. On February 17, 1600 Bruno’s sentence was carried out and his remains were dumped in the Tiber River. It was Ash Wednesday.

Giordano Bruno was no criminal in the conventional sense. He did not murder. He did not rape. Nor did he thieve, set blazes, or conspire to overthrow the secular government. He was not guilty of acts historically deemed worthy of death. Instead, Bruno’s crime was that he was an iconoclast, a divergent thinker in an era of ideological conformity. His ideas, and his refusal to follow the crowd, led to his death.

Bruno was, in many ways, a mind apart. He expanded upon the Copernican model of the universe, proposing that stars were distant suns with planets of their own, and on these planets, he surmised, there might exist other forms of life. He explored the science of memory, as well, and became a critic of the Catholic Church. “It is proof of a base and low mind for one to wish to think with the masses or majority merely because the majority is the majority,” he is often quoted as having said. “Truth does not change because it is, or is not, believed by a majority of the people.” His intractability, no doubt, assured his doom. Church leaders would suffer little dissent in those days, and their mercy was all but nonexistent.

But while his tragic persecution is extraordinary, the reason Giordano Bruno faced it is not. In truth, it is common, found in nearly every society the world over, and it is this: divergence is often seen as a threat.

Persecution has always followed divergent thinkers to varying degrees throughout history. Nowadays, thankfully, such persecution takes a decidedly less life-threatening form than what Giordano Bruno experienced in his day. This is particularly true in industrialized nations ruled by democratic methods, where certain unalienable rights are guaranteed to citizens and protected by law. (In other nations, however, while burning at the stake has gone out of vogue, the treatment that typically preceded it in the days of the Holy Inquisition has not. In these areas of the world, medieval torture is still commonly used on those who do not adhere to the norm.) But still, forms of persecution endure, even in the most advanced societies. And this persecution takes shape in the form of mistreatment, oppression, and isolation. It can also take shape in the form of categorical dismissal and ridicule. None of these things are unknown or hidden to us. Instead, they color our daily experience and everyday interactions. They are an insidious part of our societal makeup.

That divergence is often seen as worthy of punishment is not a new proposition, however. We all perceive threats to those who are different. Most of us live with the fear of being singled out hanging over our heads. We know the danger of nonconformity, unorthodoxy, and independent thought. We fear retribution for these things, even if only at an unconscious level. Why else would we take such pains to adhere to certain norms of behavior (e.g., staying in an orderly line at the grocery store, adhering to an unspoken dress-code at particular venues), if we didn’t believe there was a personal cost to noncompliance? Why do we concern ourselves with our appearance, or the perceptions of those around us, if we didn’t believe they held real-world implications? Social cohesion depends on shared values and cooperation, the thinking goes, and those who do not follow the program are, it follows, believed to be working against it. Thus, they are perceived as threats and are treated as such.

Most of us have felt the sting of rebuttal after violating some social norm. Most of us have felt excluded, isolated, or shamed after crossing a line at work, with friends, or among family. Indeed, given the rising rates of anxiety disorders, especially those stemming from interpersonal difficulties, the pain, anguish, and trauma experienced in such situations is of growing concern to all. Self-care has become a topic of popular discussion, and countless services and products are continually being rolled out to meet the needs of a snowballing population of the emotionally infirm. Furthermore, as communities grow increasingly diverse, as technology advances and develops into a homogeneous environment, and as communications become speedier and ever more consolidated, questions about how to handle nonconformists will continue to arise at an accelerating rate. Many of these issues we are struggling with today, but in the future they will become progressively importunate. Questions as simple as, What is right and what is wrong?, will continue to dog us. As well as, What is justice? Whose values matter? Whose are outdated? Who gets canceled? Who gets reeducated? Who decides the ethic for a growing social body? These are not as simple to answer as they may seem, but still it is important to make an honest effort to do so. While we may not burn people to death for contradicting religious dogma anymore, we still engage in terrible acts against those we see as Other, or those who threaten our own particular value systems. The stakes (no pun intended) are very high.

Society’s relationship with those who entertain divergent thoughts or unorthodox values should be of particular concern to those in creative industries. After all, the arts have ever been the refuge of dissidents, heretics, and trailblazers. If pressure to conform increases over time, and if the penalties for noncompliance follow suit, much of that burden will fall squarely on the shoulders of creative people. It will serve only to add further hardship in domains that have historically been difficult to navigate from the beginning. The arts will suffer.

But perhaps it is artists themselves who should lead the charge addressing these concerns. They are, by and large, intimately familiar with the torment one feels, or is made to feel, by being the alien, and they have the capacity to articulate that experience in skillful, constructive ways. Take David Grossmann, for example. His paintings serve as a metaphor for bridging division, which may well be influenced by his own history of feeling like an outsider. “Art has been an important part of my life for as long as I can remember,” he told me. “I was born in the U.S. but grew up in South America, and I struggled to find where I fit into the world around me. It was an effort to express myself in words, so art became a refuge, a language of its own.”

It was his way of reconciling his own unorthodoxy.

Like many, David Grossmann fell hard for art at a young age. “As a kid I found it really thrilling to be able to draw something and make it seem as real as possible,” he told me. “Most days I would draw for several hours because I loved it so much.” But when he was ten years old, David’s grandmother took it upon herself to do something few ever do: she decided to foster his budding creative talent. “[She] gave me my first lesson in painting with oils,” he said, “and from the age of 11 through 14 I took six hours of painting classes per week.”

After his family moved back to the U.S. and he graduated high school, David’s love of art led him to consider his possible career options. “I knew I wanted to be an artist but I did not have any clear idea of how to make a living with art,” he told me. “Out of practicality I got a degree in business first and then I went to art school.” He attended the Colorado Academy of Art in Boulder, Colorado, a small, atelier-style school that focused on drawing and painting from life. “At the time I was drawn to the rigor involved in that tradition, returning to techniques and materials that artists had used for centuries,” he said. “Although I loved that training I still did not know how I would be able to make art a career, and in my third year at the academy the school abruptly closed.” He would have to find another way, another means by which to learn how to make a career in art happen. David’s solution came by way of an experienced pro.

“I had heard that Colorado artist Jay Moore sometimes took on students and mentored them in his experience of being a professional artist,” David told me. “So I contacted him and thankfully he agreed to mentor me. It was during that mentorship that I first felt I might be able to make a living as an artist. And even though it was still another few years before I was able to paint full-time, I finally had an idea of how I might get there.”

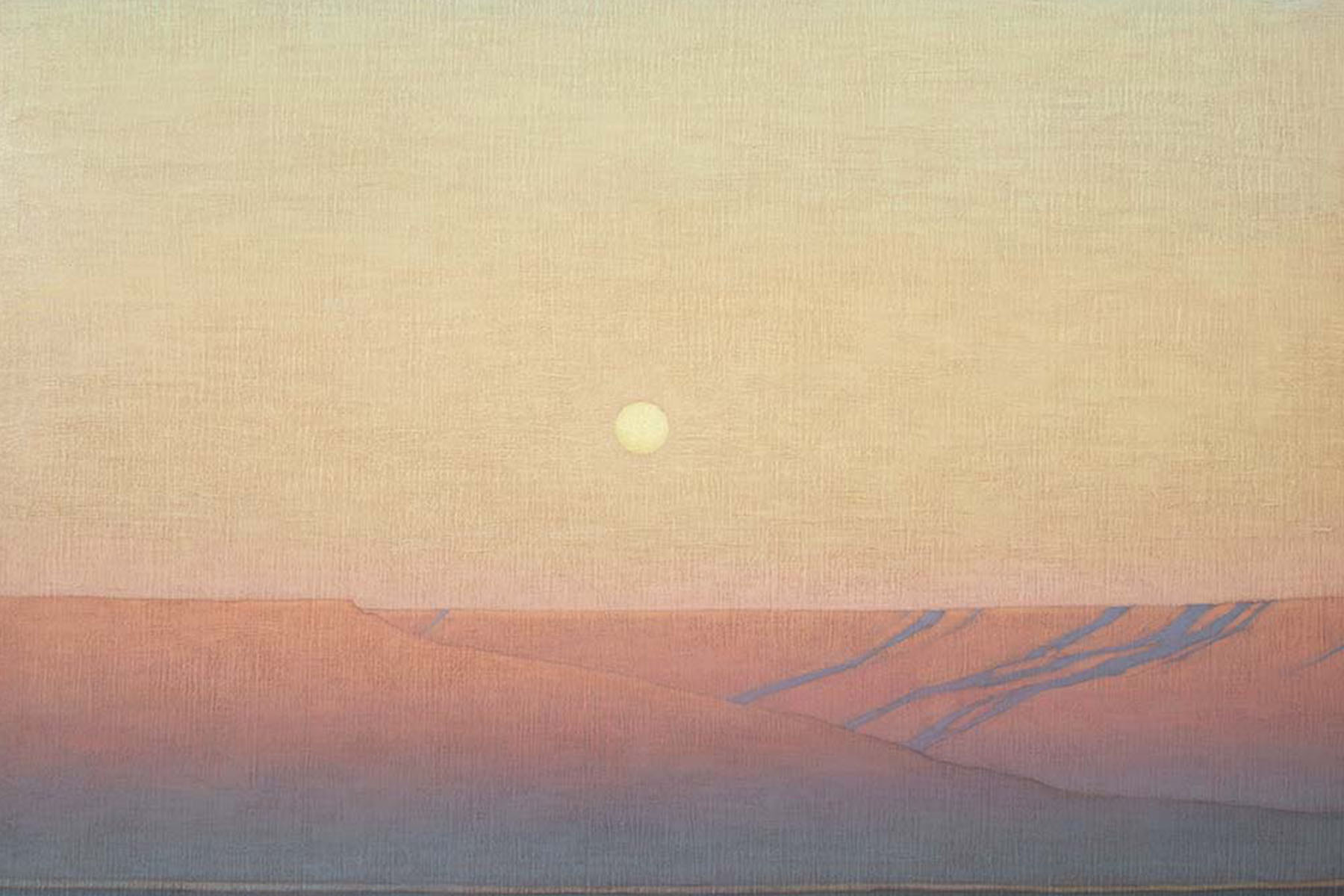

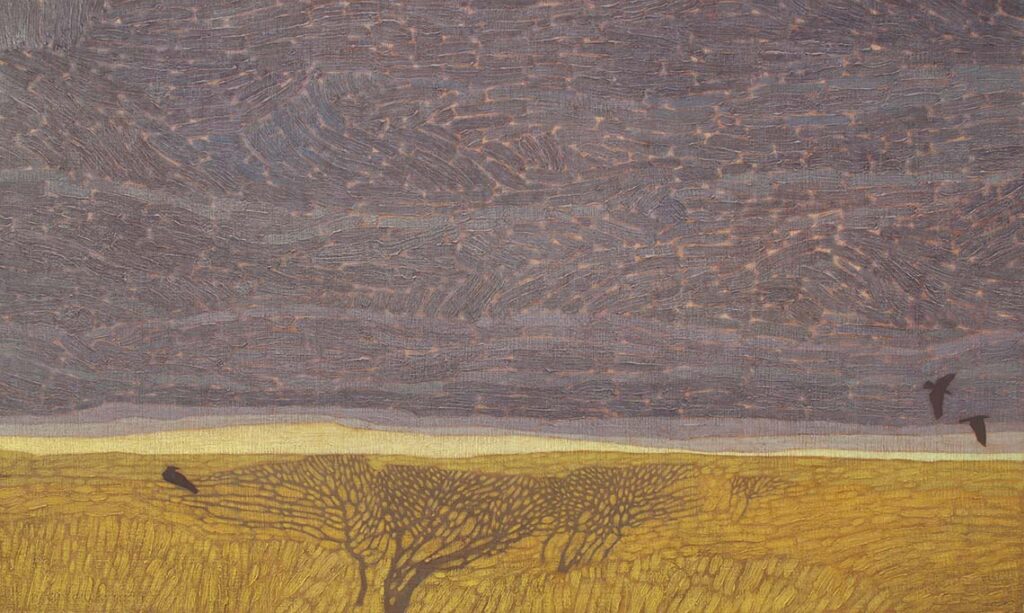

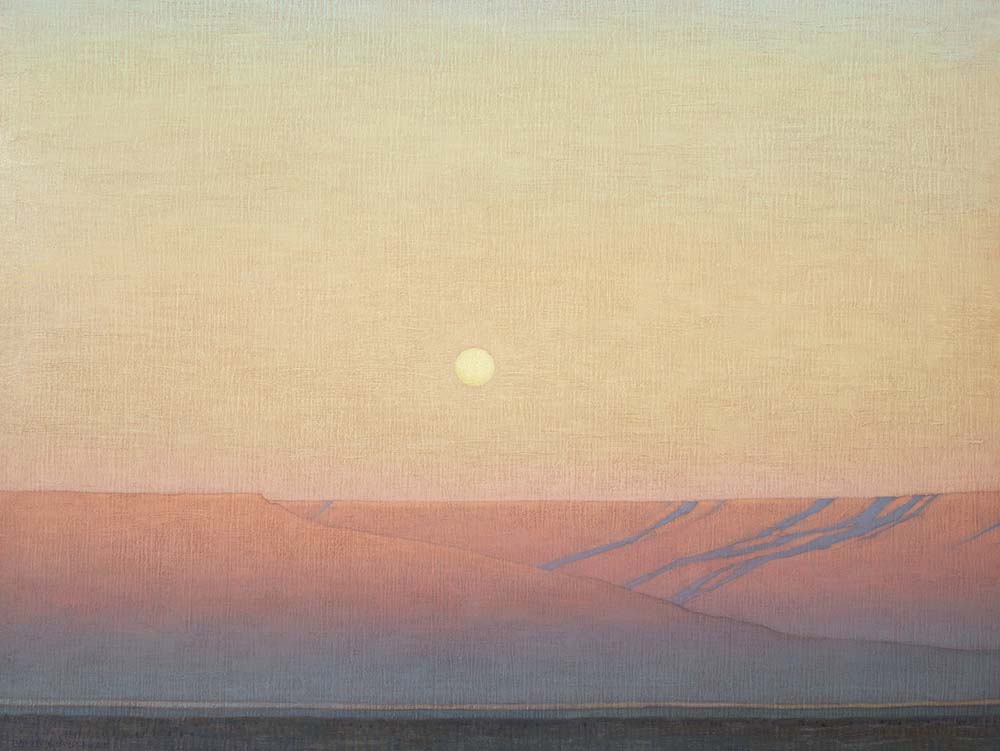

It was a path unique to him, and its influence appears in what he does today. Inspired by centuries-old processes, David’s art is created using hand-made panels upon which he meticulously develops his paintings in a time-consuming, meditative process like that of the old masters. But true to his contemporary upbringing, he weaves modern aesthetics into the work as well. The result is a style all his own, an evocative look that “[blurs] the edges between reality, memory, and imagination.” It is art that finds its own place alongside the past and present, in space that is wholly its own, yet still widely accessible to viewers. “My paintings are an invitation for viewers to slow down, observe, and connect,” David said. “I also like to think that my work is a bit of a bridge across the unnecessary division between the contemporary and traditional sides of the art world.”

It is in his role as a mediator between domains commonly thought to be in opposition that David reveals the strength of his creativity. Through this, too, he reveals the value of divergent thinking.

Because, despite what fears we may have regarding it, divergent thought is something we can all benefit from.

Neurobiological studies into the mechanisms of creativity reveal that the right hemisphere of the brain plays an important role in creative cognition. This is due to a process called neural lateralization, in which different cognitive processes are—wholly or predominantly—the responsibility of either the right or left hemisphere of the brain. There are now considerable amounts of data which lead some researchers to believe the right hemisphere of the brain is responsible for novel ideas and divergent thinking, which serve as the foundation for creative thought. Those ideas are then communicated by the left hemisphere of the brain, which specializes in sequential and analytical processes, making the emergent creative act (contrary to some popular notions) a product of the brain as a whole. This balance between distinct processing modes produces ideas that are both original and effective.

Differences in creativity can largely be explained not only by differences in specific processes found in each hemisphere, but also by the relationship between the two. The degree to which an individual favors one hemisphere over the other adds complexity to this equation too. So, then, a high degree of variability is possible, if not likely, from person to person. And while patterns of cognition may inherit, resulting in a group of people who largely think the same, the likelihood that a minority will develop significant cognitive differences is virtually guaranteed. But is that variability important? Why would we have evolved to allow for it?

As it turns out, neural lateralization has selective consequences for numerous species, including ours. If, for example, “a species tends to favor one eye/side for environmental monitoring or escape behavior, the animal that preys on it may become aware of this. It therefore becomes advantageous for a single individual within a population to do the opposite of the group (run the other way or increase vigilance in other direction).” 1 This kind of “going against the grain” produces behavior that is novel but also appropriate to the situation. Thus, having an individual who possesses divergent-style thinking is extremely valuable to the group as a whole.

And why wouldn’t that be the case? When we sit and think about it, most of us will come to the same conclusion that advancement and innovation are disruptive forces. They upend what was previously known, make irrelevant what was previously believed, or make outdated what had once been timely. By definition, conformists lack the capacity for this kind of disruption. So how else would it come about? Where does it originate? From whose minds do the mind-blowing gadgets, the transformative theories, and astonishing advancements emerge? From those who do not fit the mold, of course. From those same iconoclasts, rebels, and divergent-thinkers whose predecessors went up in columns of ash and smoke in previous eras. Burning Giordano Bruno, it’s clear to see, was much more than an individual act of brutal injustice, it was an affront to our species as a whole.

From an evolutionary standpoint, oddballs, weirdos, and freethinkers were built the way they were for very good reasons: because it was to our advantage they be that way. Understanding this may prove useful in our everyday lives. For instance, the next time you run into a person who seems helplessly nonconformist, instead of heaping derision and scorn upon them, perhaps you should be more gracious with your thoughts. Tell yourself they are the way they are for your benefit. Tell yourself they have value.

But don’t do it out of a sense of charity. Don’t do it to feel superior. That’s paternalistic. Do it because it’s true.

Many of those in the art world—especially those whose day-to-day involves significant doses of rejection—will understandably echo the call for more compassionate treatment of nonconformists. Having experienced many-a kick to the teeth themselves, they’re certainly in a position to rightfully demand it from those around them. But the art world itself isn’t so innocent in all of this. It is rife with forms of dogmatism and home to bands of merry persecutors all its own. Those who do not fit the particular standards of a given school of thought or mode of production can still find themselves derided and outcast from a community that should really have been more inclusive. Nasty debates about this movement or that aren’t uncommon. Elitist dismissals of those whose work steps outside the bounds is the norm. Hatred, jealousy, and hyper-competition abound. For a domain that claims to understand the value of unconventionality and nonconformity best, it still harbors unnecessary, fearful assumptions about it. Even in a world of divergent-thinkers, being an iconoclast and a freethinker is still seen as a threat. Strange.

David Grossmann is an artist whose work directly addresses those issues, albeit in his own gentle way. A Grossmann painting is a lyrical call for introspection and conciliation, like two beckoning hands extended in opposite directions, and its message is crafted as an appeal to viewers and industry-members alike. “The mainstream art world sometimes sees landscape paintings as irrelevant, a thing of the past,” David told me. “I wonder, though, what could be more relevant than the earth that sustains us, especially in this age of growing environmental concern? Landscape paintings can turn us back to an appreciation of what we treasure most in nature, and hopefully spur us to protect and honor it. Even that label of Landscape Painting can feel problematic because any work of art that is made from the heart transcends the labels with which we try to contain it. Heartfelt paintings of a landscape or a heartfelt abstraction can both connect with us in the same way.”

This openness is what gives David’s work power, and it’s something he encourages other artists to model as well. “Hang on to the sense of wonder that drives you as an artist,” he told me. “That childlike ability to marvel at the world around us with open curiosity is fragile and easily drowned out.”

So true.

Our modern lives are crowded with burdens. Wage stagnation and contraction is a growing concern for many. The social safety net, which appears more like an illusion each passing day, adds additional strain. Throw in a dash of government gridlock, a sprinkling of conspiracy, and a generous helping of economic hardship across the board and it’s a wonder most of us don’t walk around with poisonous bile streaming perpetually out our mouths. Understandably, what most people want right about now is normalcy. They want the comfort of the known, the familiar, the conventional. The unorthodox is unwelcome. It is heretical and dangerous. And if things persist along this trajectory, it will be seen progressively more and more as a menace that needs to be purged. As we know, that won’t bode well for any of us. Not for artists. Not for freethinkers. Not for society as a whole. We must find it in ourselves to overcome the fear, the hostility, and the repudiation of that which is different and new and strange. Luckily, artists can help us with that. They can help bridge the divide for us, and they can do it in ways that leave us attuned to a more constructive view of the world around us.

But while unorthodoxy can be useful to us all, don’t mistake this as an appeal for unrestrained acceptance. Absolutely, there are forms of heterodoxy that are harmful, divisive, and dangerous. There are those whose iconoclastic tendencies are rooted in anger, cynicism, and bad faith. There are some who simply want the world to burn, and they take perverse pleasure in kindling the flames. We shouldn’t mistake their intentions or the quality of their character. They are broken people and we must be wary of them. And perhaps a metric we can use to spot those of ill intent is one that revolves around purpose. Is what they do, or what they propose, meant to build a freer, more open, more tolerant society? Or do they seek to choke expression, limit movement, or establish a system of unfair advantages? It may take practice, but you can spot the difference between someone who seeks to help you and those who seek to harm you. But often, that ability comes only after one has found the courage to look beyond one’s own interests and when one makes an honest attempt to understand the interests of others, and those of the wider community. And in this, we can again turn to art, and to those, specifically, whose work is clearly meant to be a balm in troubled times. Through their work we are shown how to make the necessary space required to move forward in more meaningful, productive ways.

The work of David Grossmann is of that type.

“So much of our society is fast-paced, mass-produced, and distracting,” he told me. “I hope that my work might convey a sense of peace and contemplation.”

Sit with his paintings and see for yourself. Let their subtlety and calm absorb you. Let their lyricism transport you. Observe how they transcend simplistic labels and problematic dogma. Allow them to wash away your fear, your assumptions, and whatever stringent ideals you have that cause unnecessary harm to you and those around you.

You will understand the true value of unorthodoxy then.

And, perhaps, when the firelight again begins to flicker, there’ll be no bodies twisting in the flames. It will serve only to bring us all warmth and light.

David Grossmann’s work can be found on his website, as well as a number of galleries, including: Altamira Fine Art, Gallery 1261, Jonathan Cooper Gallery, Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Oh Be Joyful Gallery, and Simpson Gallagher Gallery.

Sources:

- Kaufman, A., Kornilov, S., Bristol, A., Tan, M., & Grigorenko, E. (2010). The Neurobiological Foundation of Creative Cognition. In J. Kaufman & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 216-232). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511763205.014

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.